Researchers have uncovered traces of rice beer dating back 10,000 years at the Shangshan site in Zhejiang Province, China.

This discovery, published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS), offers a glimpse into one of the earliest known examples of brewing in East Asia.

The study, a collaboration between Stanford University, the Chinese Academy of Sciences, and the Zhejiang Provincial Institute of Cultural Relics and Archaeology, reveals how the Shangshan people combined early rice agriculture with brewing techniques to create fermented beverages.

The research team analyzed 12 pottery fragments from the Shangshan site, which dates back 10,000 to 9,000 years.

These fragments came from vessels used for fermentation, cooking, storage, and serving.

By examining the residues on the inner surfaces of the pottery, scientists discovered evidence of brewing.

“We studied the microscopic remains like starch granules, phytoliths (plant silica), and fungi from the pottery to understand its purpose,” explained Prof. Liu Li of Stanford University, the lead author of the study.

The analysis showed a significant presence of rice phytoliths, indicating that domesticated rice was a key food source for the Shangshan people. They also found rice husks and leaves were used to make pottery, highlighting the importance of rice in daily life and culture.

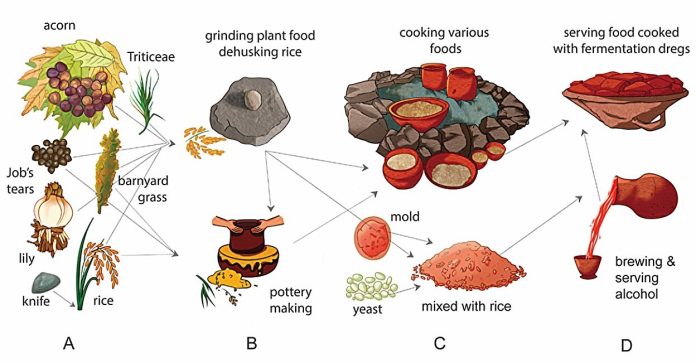

The pottery fragments contained traces of starch from rice and other plants like Job’s tears, barnyard grass, acorns, and lilies.

Many of these starches showed signs of enzymatic degradation and gelatinization, which occur during fermentation.

The team also identified fungal remains, including Monascus molds and yeast cells, which are crucial for fermentation. These fungi are still used in traditional Chinese brewing methods today, such as making red yeast rice wine (hongqujiu).

Interestingly, the fungal remains were more concentrated in globular jars compared to cooking pots or processing basins. This suggests that the jars were specifically designed for brewing rice beer.

The findings suggest that rice beer was deeply connected to the Shangshan people’s way of life. Rice farming was just beginning during this period, and the warm, humid climate of the early Holocene likely made fermentation easier.

“Domesticated rice provided a steady resource for brewing, and the favorable climate supported the growth of fungi needed for fermentation,” said Prof. Liu.

The researchers ruled out the possibility of contamination by analyzing soil samples from the site. They found far fewer starch and fungal remains in the soil compared to the pottery residues, confirming that the evidence was directly related to brewing activities.

To further support their findings, the team conducted modern fermentation experiments using rice, Monascus molds, and yeast. The results matched the fungal traces found on the ancient pottery, validating their conclusions.

The study suggests that rice beer played an important role in Shangshan society. It was likely used in ceremonies and feasts, which may have strengthened community bonds and encouraged the cultivation of rice.

“This discovery sheds light on how brewing technology, agriculture, and social structures developed together in early Neolithic China,” said Prof. Liu.

The Shangshan site offers the earliest known evidence of rice-based alcoholic beverages in East Asia. This breakthrough provides a fascinating look at the beginnings of brewing, highlighting its cultural significance in shaping ancient societies.