Scientists have long known that blocked blood flow, or ischemia, can cause serious health problems like heart attacks, strokes, and peripheral artery disease.

Now, new research shows it may also make cancer grow faster by weakening the immune system in ways that resemble premature aging.

The study, led by researchers at NYU Langone Health and published in JACC: CardioOncology, found that when blood flow in the legs was restricted in mice, breast tumors grew at twice the rate compared with mice with normal circulation.

These results build on a 2020 study by the same team, which showed that ischemia during a heart attack could also accelerate cancer growth.

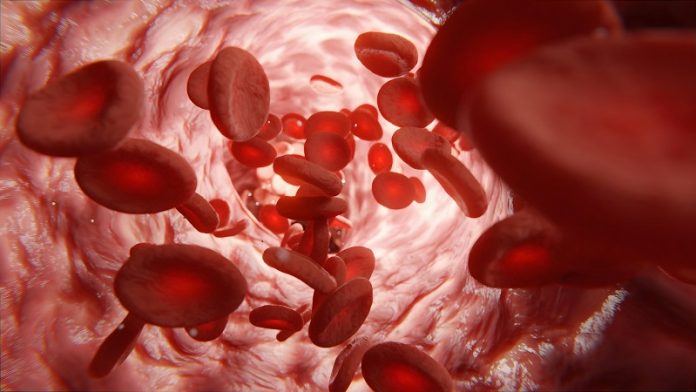

Ischemia happens when fatty deposits such as cholesterol build up in the arteries, creating inflammation and clots that limit the flow of oxygen-rich blood.

In the legs, this condition is called peripheral artery disease, which affects millions of Americans and increases the risk of heart attack and stroke.

The new findings suggest that it may also worsen cancer by reshaping how the immune system works.

According to senior author Dr. Kathryn J. Moore, impaired blood flow appears to fuel cancer growth no matter where it occurs in the body.

This highlights the importance of managing cardiovascular and metabolic risk factors—such as high cholesterol, obesity, and diabetes—not only for heart health but also as part of cancer treatment and prevention.

The researchers discovered that restricted blood flow changes how stem cells in the bone marrow produce immune cells.

Normally, the immune system maintains a careful balance. It can increase inflammation to fight infections and cancer cells, then reduce it once the threat has passed to avoid harming healthy tissues.

This balance depends on a mix of immune cells: some that activate the immune response, and others that help shut it down when no longer needed.

But with ischemia, this balance is disrupted. The bone marrow shifts toward making more “myeloid” cells, including monocytes, neutrophils, and macrophages, which are better at suppressing inflammation than fighting cancer.

At the same time, it produces fewer lymphocytes, such as T cells, which are crucial for mounting strong anti-tumor defenses.

Inside the tumors, a similar pattern emerged. Cancerous tissues accumulated more immune-suppressing cells, such as regulatory T cells and certain types of macrophages, that shield tumors from attack. These changes created a more cancer-friendly environment, allowing tumors to grow more quickly and resist immune surveillance.

The study also showed that these effects were long-lasting. Reduced blood flow not only changed the types of immune cells produced but also reprogrammed their genetic activity.

Hundreds of genes involved in immune defense were switched off, while the structure of chromatin—the protein scaffolding that regulates access to DNA—was reorganized, locking cells into a state less capable of fighting cancer.

First author Dr. Alexandra Newman explained that ischemia essentially reprograms the immune system in a way that mimics aging, making it less effective against tumors.

This discovery could lead to new approaches in cancer care, such as earlier screenings for patients with peripheral artery disease and treatments that target harmful inflammation before it accelerates cancer growth.

The researchers hope future clinical studies will explore whether existing therapies designed to reduce inflammation can help counteract these immune changes. If successful, such strategies could improve cancer outcomes for patients living with cardiovascular disease and circulation problems.

If you care about health, please read studies about the best time to take vitamins to prevent heart disease, and vitamin D supplements strongly reduce cancer death.

For more health information, please see recent studies about plant nutrient that could help reduce high blood pressure, and these antioxidants could help reduce dementia risk.