A team of researchers at the U.S. Department of Energy’s Oak Ridge National Laboratory (ORNL) has made a major leap forward in electric vehicle (EV) battery technology.

By changing one important battery component—the current collector—they’ve found a way to make EV batteries charge faster, last longer, cost less, and reduce fire risk, all while using fewer scarce metals like copper.

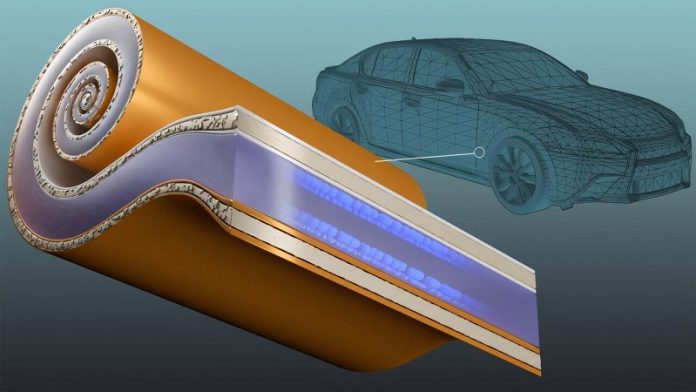

The current collector is the part of the battery that moves electricity from the battery’s core materials out to power the car.

Typically, these collectors are made of solid copper and aluminum, which are heavy, costly, and contribute to supply chain issues.

In EVs, the added weight from these metals means more energy is needed just to move the car.

Now, the ORNL team, working with a company called Soteria Battery Innovation Group, has developed a new version of the current collector.

It’s made of a thin plastic layer sandwiched between ultra-thin layers of copper or aluminum. This change may sound simple, but it has a huge impact.

The new component cuts the use of copper and aluminum by up to 85%, which helps reduce costs and lowers dependence on hard-to-source materials.

What’s more, this lightweight design means batteries can pack in more energy—27% more, in fact. That means longer trips on a single charge and a battery that can restore 80% of its power in just 10 minutes.

Even after thousands of fast-charging cycles, the battery still performs well, solving a common problem where quick charging usually shortens battery life.

Safety also gets a big upgrade. The plastic layer in the new current collector acts like a tiny circuit breaker inside the battery.

If there’s a short circuit, the heat melts the plastic, which pulls away the metal and stops the flow of electricity—helping prevent fires. According to Soteria’s CEO Brian Morin, this safety feature could eliminate 90% of battery fires caused by internal short circuits.

To prove the technology can work in real-world production, ORNL scientists built small coin-sized and pouch-style batteries using the same machines that manufacturers use. Even though the new material is thinner and more prone to wrinkling, they figured out how to make it work smoothly in standard roll-to-roll manufacturing.

This breakthrough, recently published in the journal Energy & Environmental Materials, could help electric vehicles become cheaper, safer, and more widely available—while easing the strain on global metal supplies and speeding up the switch to clean transportation.

Source: ORNL.