New research has uncovered surprising insights into the history of dogs in the Americas, showing that these loyal animals traveled slowly alongside humans as they spread farming and new ways of life across the continent thousands of years ago.

Led by Dr Aurélie Manin from the University of Oxford’s School of Archaeology, an international team of scientists studied the ancient DNA of 70 dogs, both modern and archaeological, from Central Mexico all the way to Chile and Argentina.

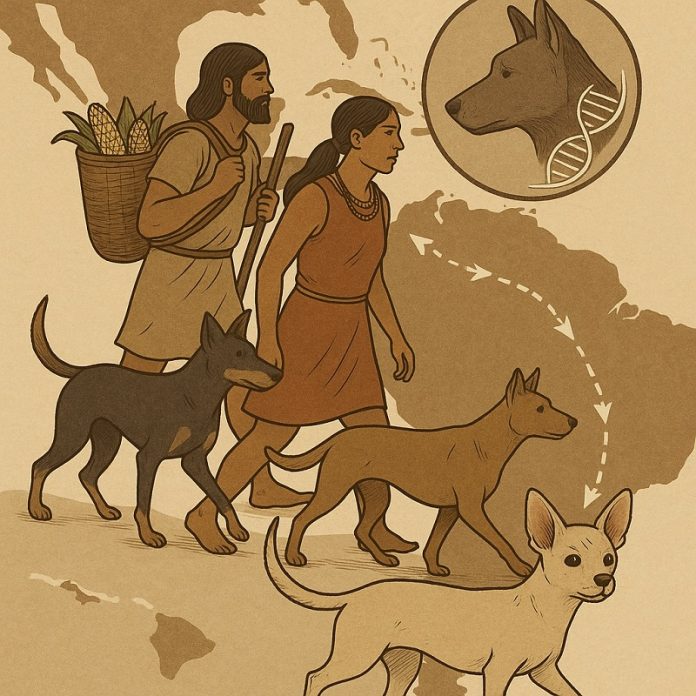

By looking at complete mitochondrial genomes (which are passed down through the mother), the team discovered that nearly all dogs in Central and South America before European contact came from a single maternal lineage.

This lineage had split from dogs in North America after humans first entered the continent.

Instead of spreading quickly, dogs made a much slower journey through the Americas, moving gradually over thousands of years.

This slow movement, called “isolation by distance,” meant dogs and people had time to adapt to new environments together.

The study shows that this journey happened between 7,000 and 5,000 years ago, alongside the spread of maize (corn) farming by early communities.

What makes this even more remarkable is that dogs were likely more than just companions—they were part of everyday life in early farming societies.

Their presence reflects how human migration and agriculture were closely tied to the animals people brought with them. While dogs today are often seen as pets, in ancient times, they played important roles in community life, travel, and survival.

Sadly, after European colonists arrived, many of these early dog lineages were replaced by European breeds. However, the research found that some modern Chihuahuas still carry rare traces of DNA from their ancient Mesoamerican ancestors. This shows that the legacy of the first American dogs lives on, especially in breeds that originated in those regions.

Dr Manin says the findings highlight how early farming societies helped shape the spread of dogs, not just in the Americas but likely elsewhere in the world. The slow pace of this spread is unusual for domestic animals and suggests a close and unique bond between humans and dogs in early agricultural life.

The full study, titled Ancient dog mitogenomes support the dual dispersal of dogs and agriculture into South America, was published in Proceedings of the Royal Society B.

Source: University of Oxford.