Paleontologists from the University of Leicester have uncovered key evolutionary changes that allowed pterosaurs, the first flying vertebrates, to grow to enormous sizes.

These prehistoric reptiles, famous for soaring through the skies during the Mesozoic era (252–66 million years ago), didn’t just fly—they also lived on the ground, and this played a major role in their evolution.

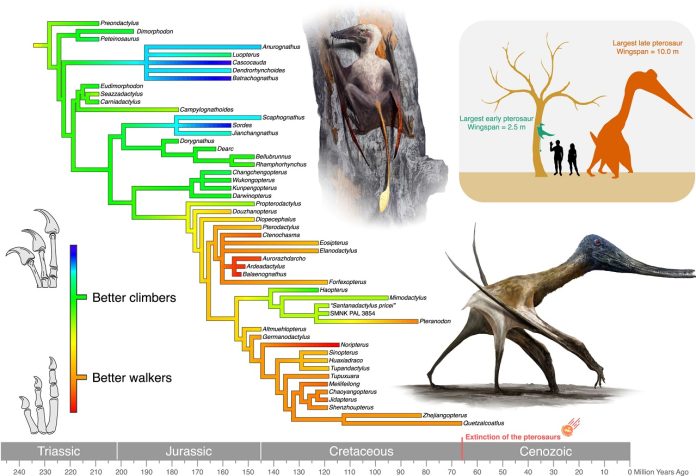

In a study published on October 4, 2024, in Current Biology, researchers at the Center for Paleobiology and Biosphere Evolution investigated pterosaur fossils from around the world, focusing on the hands and feet.

They discovered that early pterosaurs were small and specialized for climbing trees, using their sharp claws to cling to vertical surfaces.

But later in their evolution, pterosaurs adapted to life on the ground, which allowed them to grow much larger, with some species developing wingspans of up to 10 meters.

According to lead author Robert Smyth, early pterosaurs had long claws on their hands and feet, much like today’s climbing animals such as woodpeckers and lizards.

These adaptations made them great climbers, allowing them to live in trees and hunt insects and small animals. However, because clinging to trees is easier for smaller, lighter animals, these early pterosaurs remained relatively small in size.

This all changed in the Middle Jurassic period, when pterosaurs began to adapt for walking on the ground.

Their hands and feet evolved to look more like those of ground-dwelling animals, with shorter claws that were better suited for walking rather than climbing. This shift opened up new habitats and feeding opportunities, allowing pterosaurs to escape the size limitations of tree-climbing and grow to much larger sizes.

Dr. David Unwin, a co-author of the study, explained that the early pterosaurs’ hind limbs were connected by a membrane used for flight, which made walking and running difficult. In later pterosaurs, this membrane separated, allowing each leg to move independently. This change, combined with the new shape of their hands and feet, greatly improved their ability to move on land.

This newfound mobility allowed pterosaurs to explore different environments and develop unique feeding strategies.

Some species even evolved hundreds of tiny teeth for filter-feeding, similar to how modern flamingos eat today—except pterosaurs were doing this 120 million years before flamingos even existed!

The researchers believe this discovery highlights the importance of studying not just pterosaur flight, but also how they moved and lived on the ground.

By doing so, we can better understand the full story of these remarkable creatures and how they fit into ancient ecosystems.

Pterosaurs lived alongside dinosaurs and other reptiles, but instead of competing directly with them, they adapted to fill unique ecological niches that required both flying and walking abilities.

This flexibility in how they lived and moved was key to their success, allowing them to become some of the largest flying animals in Earth’s history.

Source: University of Leicester.