A new study has shed light on the flight abilities of ancient pterosaurs, revealing that while some of these giant creatures flapped their wings, others soared like vultures.

The research, published in the Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology, shows that different species of pterosaurs had different flying styles, based on the internal structures of their wing bones.

Pterosaurs, flying reptiles that lived during the time of the dinosaurs, have long puzzled scientists.

The largest pterosaurs could have wingspans of up to 10 meters (about 33 feet), leading some experts to question whether they could fly at all.

But thanks to newly discovered fossils, scientists now believe that not only could these giant creatures fly, but they may have flown in different ways depending on their size and structure.

A team of scientists from the University of Michigan, Yarmouk University in Jordan, the Saudi Geological Survey, and the Natural Resources Authority in Jordan studied two different species of pterosaurs that lived during the Late Cretaceous period, about 72 to 66 million years ago.

These fossils were found in nearshore environments that once existed on the ancient landmass of Afro-Arabia, which included parts of modern-day Africa and the Arabian Peninsula.

The fossils were incredibly well-preserved in three dimensions, something that is very rare for pterosaur bones.

Pterosaur bones are hollow and fragile, and they are usually found flattened. Lead researcher Dr. Kierstin Rosenbach, from the University of Michigan, explained that the team was surprised to find such well-preserved fossils.

“We were extremely lucky to find these 3D-preserved bones,” Dr. Rosenbach said. “Pterosaur bones are very fragile, and it’s rare to find them in such good condition.

This gave us a chance to see the inside of the bones using CT scans, something that isn’t often possible.”

Using high-resolution CT scans, the team examined the internal structure of the pterosaurs’ wing bones. The scans revealed two very different flight styles.

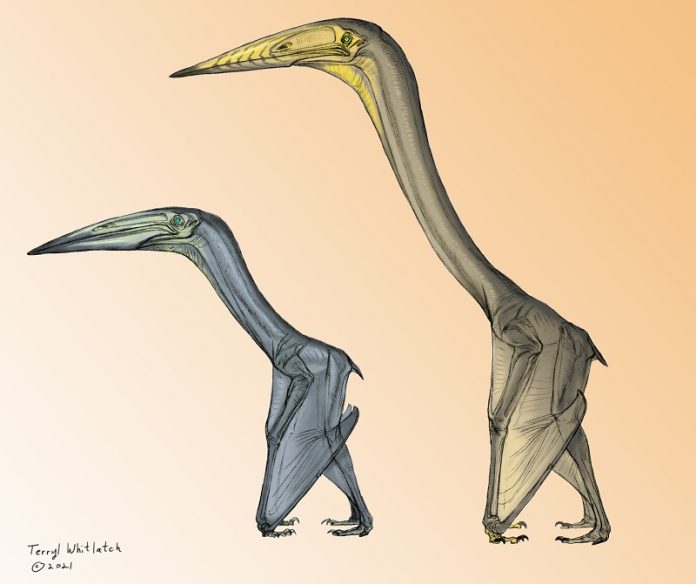

One of the species studied was Arambourgiania philadelphiae, a giant pterosaur with a wingspan of 10 meters.

The CT scans showed that the inside of its humerus (the bone in the upper wing) had spiral ridges. These ridges are similar to those found in the wing bones of vultures, which are known for their ability to soar in the air for long periods without flapping much.

This suggests that Arambourgiania was also a soaring animal, using air currents to stay in flight with minimal effort.

The second species studied was a new-to-science pterosaur named Inabtanin alarabia. This pterosaur had a smaller wingspan of about five meters and had a very different internal bone structure.

The CT scans showed crisscrossing struts inside the bones, similar to what is seen in modern birds that flap their wings.

This suggests that Inabtanin used flapping flight, relying on the strength of its wings to stay in the air, much like many birds today.

The discovery of these two different flight styles is exciting because it opens up new questions about how these animals lived and evolved.

Dr. Rosenbach believes that flapping was likely the original flight style, with soaring evolving later in species that lived in environments where it was more beneficial, such as over open oceans.

“If we look at other flying animals, like birds and bats, flapping is by far the most common flight style,” Dr. Rosenbach explained. “Even birds that soar or glide still need to flap their wings to take off and maintain flight. This leads us to believe that flapping flight was the default for pterosaurs, and soaring likely evolved later if it was useful for a particular environment.”

This study also highlights how much we still have to learn about pterosaurs. While we have learned a lot about their flight by comparing them to modern birds and bats, there is still much more to uncover.

The detailed examination of the internal structures of pterosaur bones provides new insights into how these creatures lived and flew. The team hopes that their work will encourage further studies of pterosaur fossils and help scientists better understand these remarkable animals.

“Pterosaurs were the first and largest vertebrates to evolve powered flight, but they are the only major flying group that has gone extinct,” said Dr. Rosenbach.

“We hope that this study will lead to more research on the relationship between bone structure and flight ability in pterosaurs, and ultimately give us a clearer picture of their flying abilities.”

The study not only answers questions about how some pterosaurs flapped while others soared, but also opens up new opportunities for exploring the mechanics of flight in ancient animals.

With continued research, scientists hope to unlock even more secrets of these giants of the sky.

Source: Taylor & Francis.