Ever since the first Neanderthal bones were found in 1856, people have been curious about these ancient relatives.

How different were they from us?

Did they get along with our ancestors? Fight them? Fall in love with them? The discovery of Denisovans, another ancient human group in Asia, added even more questions.

Now, an international team of geneticists and AI experts is rewriting the history of our interactions with these ancient humans.

Led by Joshua Akey, a professor at Princeton University, the researchers have uncovered evidence of multiple periods of genetic mixing between modern humans, Neanderthals, and Denisovans.

This suggests that our connection with these ancient groups was much closer than previously thought.

“This is the first time we’ve identified multiple waves of mixing between modern humans and Neanderthals,” said Liming Li, a professor in China who worked on this research in Akey’s lab.

For most of human history, modern humans and Neanderthals had contact. Our direct ancestors split from the Neanderthal family tree about 600,000 years ago and developed our modern traits about 250,000 years ago.

From then until Neanderthals disappeared around 30,000 years ago, they interacted with modern humans for about 200,000 years.

The results of their research were published in the journal Science.

Neanderthals, once thought to be slow and unintelligent, are now recognized as skilled hunters and toolmakers. They treated injuries with advanced techniques and were well adapted to cold European climates.

All these groups—Neanderthals, Denisovans, and modern humans—are considered humans. However, to avoid confusion, scientists use the terms Neanderthals, Denisovans, and modern humans to refer to these different groups.

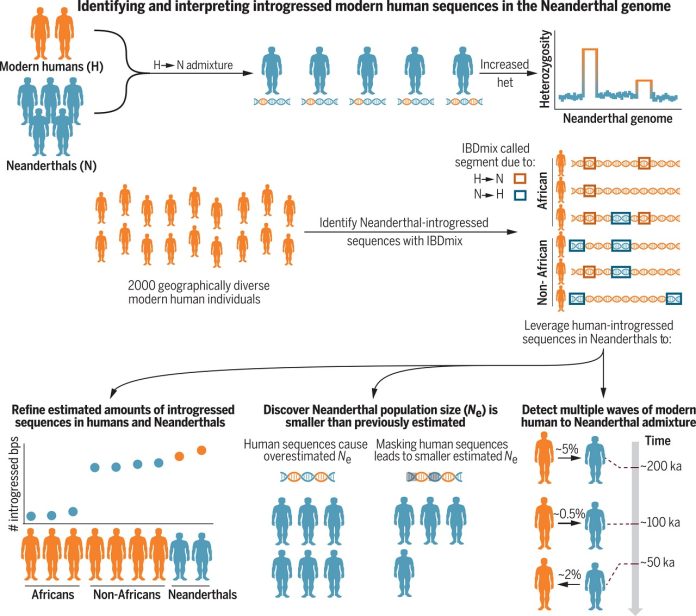

Using genomes from 2,000 living people, three Neanderthals, and one Denisovan, Akey’s team mapped the gene flow between these groups over the past 250,000 years. They used a genetic tool called IBDmix, which uses machine learning to decode genomes. Previous studies compared human genomes to a “reference population” of modern humans with little or no Neanderthal or Denisovan DNA. But Akey’s team found that even these reference groups had some Neanderthal DNA, likely carried by travelers and their descendants.

With IBDmix, they discovered three waves of contact: the first about 200-250,000 years ago, the second 100-120,000 years ago, and the largest 50-60,000 years ago.

This contrasts sharply with previous beliefs that modern humans evolved in Africa 250,000 years ago, stayed there for 200,000 years, and then left Africa 50,000 years ago. Akey’s research shows that modern humans have been moving out of Africa and returning, encountering Neanderthals and Denisovans much earlier and more frequently than we thought.

This new understanding aligns with archaeological findings suggesting cultural and tool exchanges between these groups.

Li and Akey’s key insight was to look for modern-human DNA in Neanderthal genomes, rather than the other way around. They realized that offspring from the earliest Neanderthal-modern human matings likely stayed with Neanderthals, leaving no genetic trace in today’s humans. By incorporating Neanderthal DNA into their studies, they discovered earlier migrations that were previously hidden.

Another significant finding was that the Neanderthal population was smaller than previously believed. Using IBDmix, they showed that much of the genetic diversity in Neanderthals came from mixing with modern humans, leading to a revised estimate of about 2,400 breeding individuals, down from 3,400.

These discoveries suggest that Neanderthals didn’t go extinct in the traditional sense but were gradually absorbed into modern human populations. “Neanderthals were teetering on the edge of extinction for a long time,” Akey said. “Modern humans gradually overwhelmed them, incorporating them into our populations.”

This research paints a picture of our ancient ancestors as constantly on the move, mixing with Neanderthals and Denisovans, and sharing more history with these groups than we ever realized.