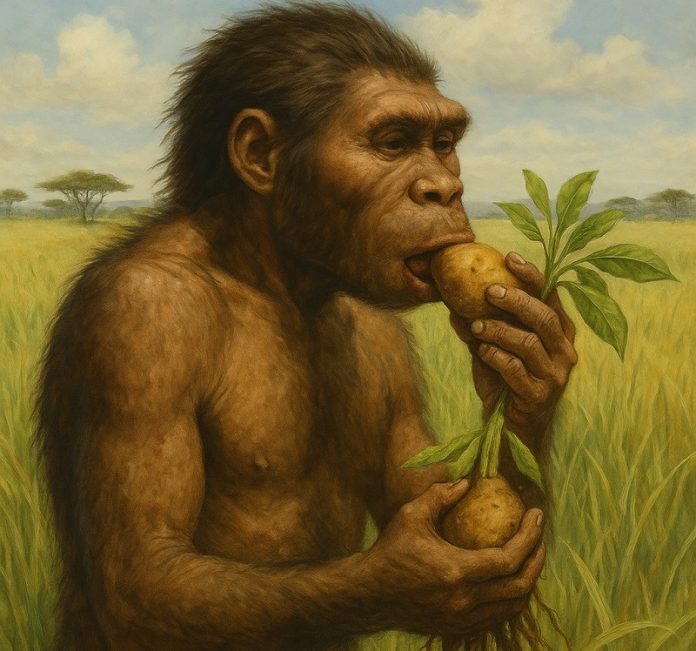

Long before humans had teeth suited for chewing tough plants, our ancient ancestors had already developed a taste for them.

A new study led by Dartmouth University reveals that early humans began eating grasses and starchy underground plant parts well before their bodies evolved to handle these foods efficiently.

The findings, published in Science, suggest that behavior—not just physical traits—played a powerful role in human evolution.

As early humans moved from forested areas into grassy landscapes, they needed new, reliable sources of energy.

Grains and underground plant parts like tubers, bulbs, and corms offered a rich supply of carbohydrates.

But their teeth weren’t ready. It wasn’t until nearly 700,000 years later that molars adapted to better handle these tough, fibrous foods. Still, humans continued to eat them—and thrive.

To uncover this evolutionary story, researchers examined the fossilized teeth of ancient hominins—human ancestors—dating back nearly 5 million years.

By analyzing the chemical signatures left behind in these teeth, they could tell what kinds of plants individuals had eaten.

The evidence pointed to grasses and sedges, collectively known as graminoids, being a significant part of early diets.

Luke Fannin, the study’s lead author, says this is a clear sign of what scientists call “behavioral drive.”

That means early humans changed their habits and diets in response to environmental challenges, even before their bodies evolved to support those changes.

“We found that behavior was a driving force in human evolution,” Fannin explains. “Our ancestors were incredibly flexible, able to adapt quickly to new surroundings—even when their physical traits lagged behind.”

The research team also looked at the teeth of other primates that lived around the same time, including large baboon-like monkeys called theropiths and smaller, leaf-eating colobines. All three species showed signs of shifting away from fruits and insects toward tougher plants between 3.4 and 4.8 million years ago. But only hominins made a later dramatic shift—around 2.3 million years ago.

At that time, carbon and oxygen isotopes in hominin teeth changed sharply. This change suggests they began relying on underground plant parts, which store high amounts of carbohydrates and water. These foods offered a safer, year-round energy source and may have fueled the development of larger brains and growing communities.

With stone tools, early humans could dig for tubers and bulbs with little competition from other animals. These underground resources may have given them a big advantage during periods when food above ground was scarce.

Fascinatingly, even as their molars got longer to help grind these foods, overall tooth size shrank. It wasn’t until Homo habilis and Homo ergaster appeared about 2 million years ago that the shape and size of teeth began to adapt more rapidly, better suiting them for eating roasted or cooked foods, including tubers.

Senior researcher Nathaniel Dominy points out that grasses are still central to human life today. “Our entire global economy depends on grass plants like rice, corn, and wheat,” he says. “It all started with early humans doing something completely unexpected—eating plants they weren’t yet built to eat.

That behavior may be what set us apart from all other primates and helped shape the course of human history.”