A new study has found that mammals have evolved to eat ants and termites at least 12 different times since dinosaurs went extinct.

After the asteroid wiped out most life on Earth about 66 million years ago, ecosystems began to change—and ants and termites started to thrive. This opened the door for some mammals to evolve special skills to eat them.

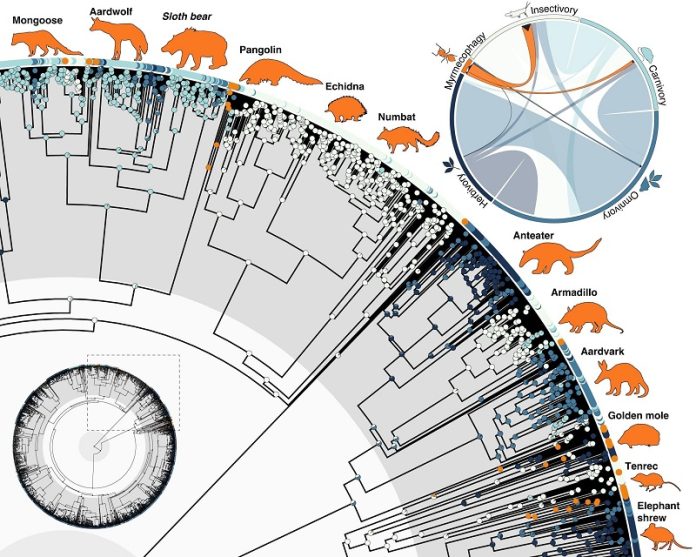

Scientists call this diet myrmecophagy, which means feeding mostly on ants and termites. Over 200 mammal species eat these insects today, but only around 20 species rely on them as their main or only food.

These “true” ant-eaters include animals like the giant anteater, aardvark, and pangolin. They all have things in common: long sticky tongues, powerful claws for digging into nests, and fewer or no teeth.

The research, published in the journal Evolution, was the first to explore how many times this extreme diet developed independently in mammals.

Using diet records for over 4,000 mammal species, the researchers mapped dietary habits onto the mammal family tree and found at least 12 separate cases of mammals evolving to specialize in ants and termites.

What’s surprising is how widespread this pattern is. These ant-eating mammals come from all three major mammal groups: monotremes (like the echidna), marsupials (like numbat), and placentals (like pangolins).

However, they didn’t evolve evenly across groups. Some families, such as Carnivora (which includes dogs and bears), made the switch more often than others, even though it’s a big leap from eating large animals to tiny insects.

One reason ants and termites became such an attractive food source is that they exploded in number after the dinosaur age. In the Cretaceous period, they were rare. But by about 23 million years ago, they made up over a third of all insects on Earth. Their huge numbers created an opportunity for mammals willing to specialize.

But becoming an ant specialist comes with trade-offs. Ants and termites are low in calories, so even small ant-eaters need to consume tens of thousands a day. Some species eat hundreds of thousands in a single night.

And once a mammal becomes an obligate ant-eater, it usually doesn’t go back. In fact, almost all lineages that adopted this diet stayed that way. Only one group, the elephant shrew genus Macroscelides, eventually switched back to a more flexible diet.

That kind of dietary commitment can limit a species’ ability to adapt if their food source disappears.

Researchers warn that such specialization may lead to an evolutionary “dead end.” But for now, ant-eating mammals seem to be doing fine—especially since ants and termites are more widespread than ever.

In a world where social insects are thriving, these specialized feeders might just have the upper hand.

Source: KSR.