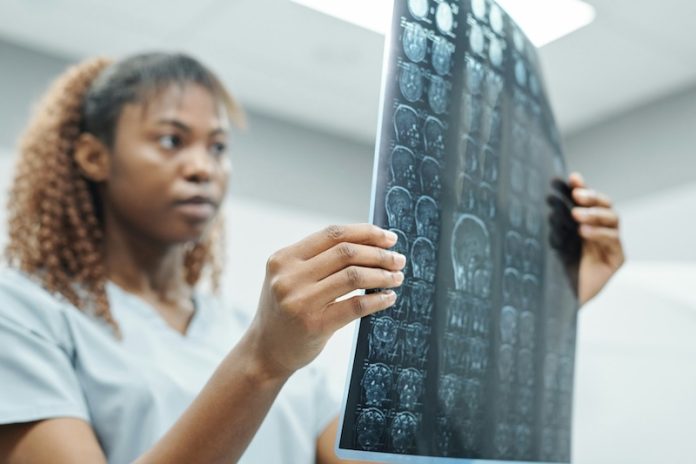

A new tool developed by scientists from Duke University, Harvard, and the University of Otago in New Zealand can now estimate how quickly someone is aging—just by looking at a single brain scan. This breakthrough could help doctors spot people at risk for diseases like dementia decades before symptoms begin.

Published in Nature Aging, the study introduces a brain-based “aging clock” called DunedinPACE of NeuroImaging (DunedinPACNI). This tool can forecast a person’s future risk of chronic illnesses, memory loss, and even early death, using just one MRI image of the brain.

Aging affects people differently. Some older adults remain sharp and active, while others become weak or forgetful earlier than expected. According to lead author Professor Ahmad Hariri from Duke University, “The way we age is not just about how many birthdays we’ve had—it’s about how our bodies and brains are holding up.”

To build the tool, researchers used data from the Dunedin Study, a long-term project tracking the health of over 1,000 people born in Dunedin, New Zealand, in the early 1970s.

For nearly 50 years, these participants have undergone regular checkups measuring everything from blood pressure to tooth decay. This allowed the scientists to track how fast each person was aging physically.

The DunedinPACNI tool was trained on brain scans from 860 of these people taken when they were 45 years old. Using patterns in the scans, the tool learned to predict each individual’s “biological aging rate”—how quickly their body is wearing down compared to others their age.

Then, the researchers tested the tool using brain scans from other studies involving people in the U.S., U.K., Canada, and Latin America. The results were impressive.

People the tool flagged as “fast agers” were more likely to score poorly on thinking and memory tests, show faster shrinkage in key memory areas of the brain (like the hippocampus), and—most importantly—were at higher risk of developing dementia and dying sooner.

In one group of people aged 52 to 89, those who appeared to be aging the fastest were 60% more likely to develop dementia in the following years. They also began showing signs of memory problems sooner than their peers.

But the effects weren’t limited to the brain. Fast agers were more frail overall and 18% more likely to develop serious conditions like heart disease, stroke, or lung problems. They were also 40% more likely to die within a few years compared to people aging at a more average pace.

Even better, the tool’s predictions held true across people of different races, income levels, and countries—suggesting it captures something universal about how the brain and body age together.

This could be a game-changer. Right now, there’s no reliable way to spot who might get Alzheimer’s or other age-related diseases before damage has already occurred. Most treatments are given too late to make a real difference.

“Drugs can’t bring a dying brain back to life,” Hariri said. But with early detection, future treatments could step in sooner—when they have a real chance to work.

The researchers hope DunedinPACNI will help scientists answer tough questions, like why some people age faster than others, and how factors like poor sleep or depression might speed up aging. The tool might also help doctors test whether lifestyle changes or new drugs can slow down aging in at-risk individuals.

Lead PhD student Ethan Whitman said the tool is not yet ready for everyday clinical use. But researchers worldwide with access to brain scans can already start using it to study aging in ways that go beyond blood tests or physical exams.

In a world where more people are living longer, yet facing rising rates of dementia and other chronic diseases, this discovery comes at a critical time. “We think of this as a powerful new way to forecast disease risk—especially Alzheimer’s,” Hariri said. The team has even filed a patent, hoping their work will become part of future health care solutions.

If you care about dementia, please read studies about low choline intake linked to higher dementia risk, and how eating nuts can affect your cognitive ability.

For more information about brain health, please see recent studies that blueberry supplements may prevent cognitive decline, and results showing higher magnesium intake could help benefit brain health.

The research findings can be found in Nature Aging.

Copyright © 2025 Knowridge Science Report. All rights reserved.