A new study reveals that some of our earliest human ancestors showed extreme differences in body size between males and females—much greater than in modern humans, and even more than in gorillas.

This finding suggests that early human relatives may have lived in highly competitive social systems, where larger males likely fought for dominance and mating opportunities, while smaller females may have had reproductive advantages due to energy demands.

The study, led by anthropologist Adam D. Gordon from the University at Albany, is published in the American Journal of Biological Anthropology.

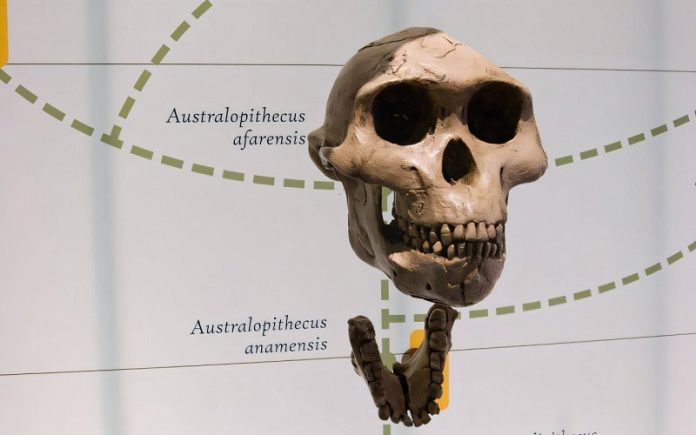

It focuses on two early hominin species: Australopithecus afarensis (which includes the famous “Lucy” fossil) and Australopithecus africanus, a closely related species from southern Africa. Both species lived more than 2 million years ago.

Using a new method designed to work around the problem of incomplete fossil remains, Gordon and his team were able to measure and compare the body sizes of male and female individuals from each species.

They found that males were significantly larger than females, particularly in A. afarensis. In fact, the size difference in this species may have been more extreme than what we see in any living great ape today.

These dramatic size differences—known as sexual size dimorphism (SSD)—can offer clues about social behavior.

In primates, high SSD usually means that males compete intensely for mates, often in hierarchical societies where one dominant male mates with multiple females. This is true for gorillas, where large males defend groups of females, and also to a lesser extent in chimpanzees.

In contrast, species like modern humans, which tend to form pair bonds and show less competition, exhibit much smaller size differences between the sexes.

The findings also suggest that early hominins experienced a wide variety of evolutionary pressures, even among species once thought to be very similar. For example, while A. afarensis had extremely high dimorphism, A. africanus showed less—closer to what we see in gorillas but still greater than in humans. This points to possible differences in mating behavior, competition, or environmental stress between the two species.

To conduct the study, Gordon used a method that estimates body size using a combination of skeletal parts—like leg and arm bones—and compares the results to modern species with known sex and complete skeletons. He also applied a statistical approach that accounts for missing or fragmented fossils, making the comparisons more accurate than in previous studies.

Importantly, Gordon checked to make sure that the size differences in A. afarensis weren’t simply the result of changes over time.

He studied fossils from the Hadar Formation in Ethiopia, covering a span of about 300,000 years, and found no clear trend of increasing or decreasing size. This strongly suggests that the variation was due to differences between males and females—not gradual evolution.

These findings add a new layer of understanding to how early hominins may have lived. While both A. afarensis and A. africanus are classified as “gracile australopiths”—generally considered to be more human-like in their body build—this study shows that their social lives may have been very different.

Gordon’s research paints a picture of early human ancestors that were shaped by intense competition, environmental stress, and a broader diversity of lifestyles than previously believed.