Sloths today are known for being slow, small, and tree-loving creatures. But their ancient relatives were nothing like them.

In fact, many extinct sloths were enormous, ground-dwelling giants that roamed across the Americas.

Now, a new study published in Science has revealed how these prehistoric sloths got so big—and why their size may have ultimately led to their extinction.

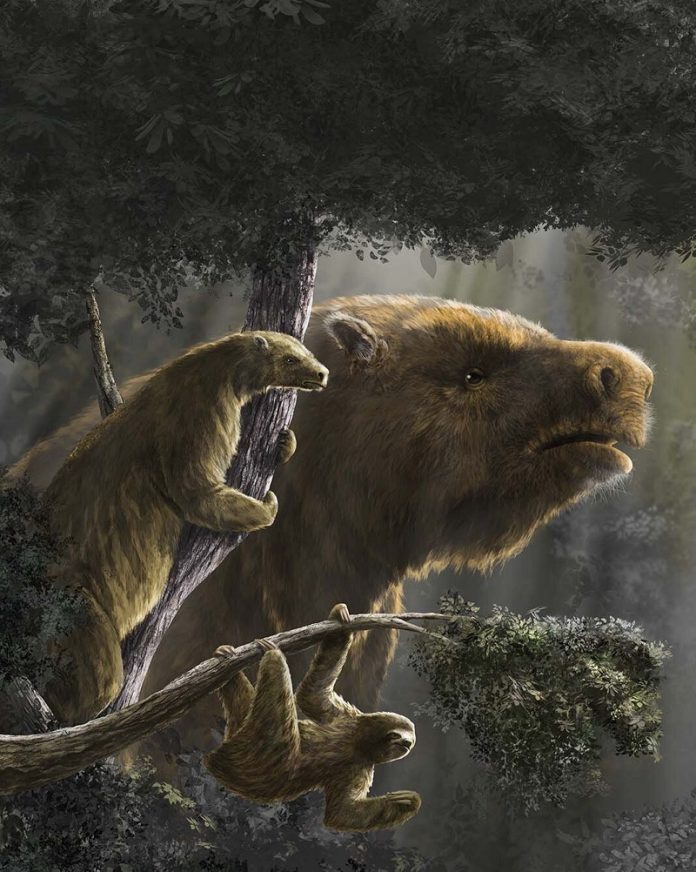

Modern sloths, which weigh around 14 pounds, spend nearly their entire lives hanging from tree branches.

But millions of years ago, there were dozens of sloth species—some so large they matched the size of elephants.

The biggest, Megatherium, tipped the scales at around 8,000 pounds and stood as tall as an Asian bull elephant.

These creatures were built like grizzly bears but much larger, using long claws to pull down tree branches and possibly carve out caves for shelter.

To uncover the mystery behind their massive size, scientists from institutions across the world, including the Florida Museum of Natural History, studied ancient DNA and more than 400 fossils from 17 museum collections.

They compared fossil shapes, body sizes, diets, and habitats, building a complete “sloth family tree” going back 35 million years. This was the first study to combine all this data to understand the evolution of sloth size.

They discovered that where sloths lived—and how the climate changed over time—played a key role in how big they became. In tree-dense environments, sloths stayed small.

Tree branches can’t hold much weight, and a fall from a tall tree can be deadly, even for sloths. That’s why tree sloths evolved to be light, flexible, and slow-moving. In contrast, sloths that lived on the ground were free to grow much larger.

Around 15 million years ago, a massive volcanic event reshaped the western United States, releasing greenhouse gases and triggering a global warming event called the Mid-Miocene Climatic Optimum. In response, sloths actually shrank.

Warmer temperatures likely caused forests to spread, offering more tree habitats and favoring smaller sizes.

But as the planet cooled again, sloths began to bulk up. The largest ground sloths emerged during the Ice Ages. Big bodies helped them survive cold temperatures, conserve water, and protect themselves from predators in open grasslands. Some even developed armor-like skin and adapted to live in the ocean.

One marine sloth species, Thalassocnus, had heavy bones for buoyancy and snouts shaped for eating seagrass, similar to manatees.

Giant sloths were highly adaptable, living everywhere from tropical deserts to frozen tundras. But their size came with a cost. While it helped them survive harsh conditions, it also made them slow and vulnerable.

About 15,000 years ago, as humans began arriving in the Americas, the massive sloths began to disappear. Too big to hide or run, they likely became easy targets for early hunters. Their tree-dwelling cousins survived longer, but not everywhere. Some sloths on Caribbean islands held out until just 4,500 years ago—around the time the pyramids were being built in Egypt—before they too went extinct after humans arrived.

This new study shows that climate change, habitat, and human activity all played a role in shaping sloth evolution.

The traits that once made ground sloths such powerful survivors—large size, slow movement, and low metabolism—eventually became their greatest weakness. Today’s tiny, tree-hugging sloths are the last survivors of a once-diverse family that included some of the most impressive mammals to ever walk the Earth.

Source: Florida Museum of Natural History.