Deep in the ocean, sea sponges grow beautiful, glass-like skeletons that are both strong and light.

These structures are made from a natural glass called silica.

Now, scientists are copying the way sea sponges build their skeletons to create tiny, powerful lenses that could lead to better imaging technology in medicine and beyond.

A team of researchers from the University of Rochester, along with scientists from the University of Colorado–Boulder, Delft University of Technology, and Leiden University, has created tiny glass lenses using bacteria.

Their findings were recently published in the journal PNAS. These new microlenses, inspired by sea sponges, could be used in high-resolution image sensors for medical tools and other devices.

A microlens is a lens so small it’s about the size of a single human cell. These lenses are used to focus and control light at a very tiny scale.

Making them has always been a challenge, requiring expensive machines and harsh conditions like high heat or pressure.

But the new lenses made by this research team are different—they’re grown naturally using bacteria, without the need for complex equipment.

Biology professor Anne S. Meyer led the project. After learning that sea sponges use an enzyme to turn silica into strong, light structures, she wondered if the same process could be used in a lab. Her team engineered bacteria to produce the same enzyme, allowing the bacteria to grow a layer of glass on their own surfaces.

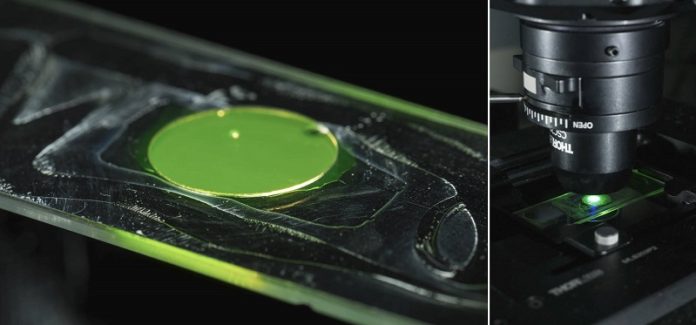

The team also developed a special microscope to test how well these bacteria-based microlenses focus light. The results were impressive.

Not only did the microlenses work, but they were also smaller than most lenses made by traditional methods. Because these lenses are made using bacteria, they are cheap and easy to produce, even at room temperature and normal pressure.

These tiny lenses could make a big impact. For example, they might help doctors see smaller details in tissues or cells during imaging, improving diagnosis and treatment.

They could also help scientists study parts of cells that are too small to be seen with regular microscopes. The fact that the bacteria stay alive even after growing their glass coating means the lenses might also respond to changes in their environment—like tiny living sensors.

The U.S. Air Force has taken interest too, awarding the team a grant to study how these microlenses behave in space.

Because they’re easy to grow without special tools, they could one day be made in space stations or other places where high-tech machines aren’t available.

Nature may have built sea sponges to survive under the sea, but now their secrets could help us see further than ever before.