This Christmas, paleontologists from the University of Leicester have shared some exciting news: they’ve reunited a family that has been separated for 150 million years!

Nearly 50 “hidden” relatives of Pterodactylus, one of the first flying reptiles, have been identified.

This discovery helps scientists better understand these fascinating creatures, from hatchlings to adults.

The story of Pterodactylus begins nearly 250 years ago when its first fossil was found in a quarry in Bavaria, Germany.

This 150-million-year-old fossil introduced the world to a group of incredible flying reptiles, the pterosaurs, which ruled the skies during the time of the dinosaurs.

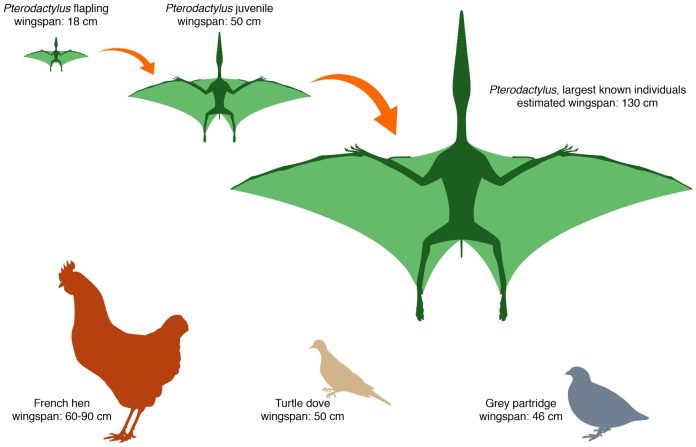

Unlike the massive pterosaurs like Pteranodon and Quetzalcoatlus, which could have wingspans over 10 meters, Pterodactylus was much smaller—only the size of a turtle dove. Despite its modest size, this discovery reshaped how we see prehistoric life.

Over the centuries, Pterodactylus has remained a favorite among scientists, who have studied its fossils to learn about its wings, diet, and growth.

However, one question lingered: how many fossils truly belong to Pterodactylus, and how many are from different species? This mystery has puzzled paleontologists for hundreds of years—until now.

A new study, published in the Journal of Systematic Palaeontology, has solved the mystery. By analyzing dozens of fossils in museums worldwide, University of Leicester paleontologists Robert Smyth and Dr. Dave Unwin discovered that nearly 50 specimens previously thought to be different species actually belong to Pterodactylus.

The secret to their discovery? UV light.

Using powerful UV torches, Smyth and Unwin made hidden details on the fossils glow. These details, found in the head, hips, hands, and feet, helped them identify which fossils were part of the Pterodactylus family.

“It was amazing to see features that were once invisible glowing in plain sight,” said Smyth, the lead researcher.

Their work has completely changed what we know about Pterodactylus. With nearly 50 examples now identified, scientists can build a detailed picture of this ancient flying reptile. They’ve even found soft tissue preserved in some fossils, revealing details like head crests, foot webs, and the shape of the wings.

The fossils also show how Pterodactylus grew. The hatchlings, nicknamed “flaplings,” were no bigger than a sparrow, yet they could fly from birth. Most fossils are from “teenagers” the size of pigeons, but fully grown adults were much larger, with wingspans over one meter.

Dr. Unwin explained, “This discovery lets us reconstruct the entire life story of Pterodactylus, from baby to adult. The UV technique we used will revolutionize how we study pterosaurs in the future.”

Thanks to this research, Pterodactylus has its place in history secured, and its family has been brought back together—just in time for the holidays.