For the first time, scientists have discovered amber on the Antarctic continent, filling a major gap in the global map of amber finds.

This remarkable discovery was made by a research team led by Dr. Johann P. Klages from the Alfred Wegener Institute and Dr. Henny Gerschel from TU Bergakademie Freiberg.

The amber was found during a 2017 expedition aboard the research icebreaker Polarstern.

Using a seafloor drill rig at a depth of 946 meters in Pine Island Bay, located in the Amundsen Sea, the team recovered sediment cores containing tiny pieces of amber.

They named it “Pine Island amber” after the discovery site, located at 73.57° South and 107.09° West. Their findings were recently published in the journal Antarctic Science.

The amber fragments offer a glimpse into the environment of West Antarctica 90 million years ago, during the mid-Cretaceous period.

According to Dr. Klages, this discovery provides more clues about how the temperate, swampy rainforests of that time functioned.

“It’s fascinating to see how all seven continents, including Antarctica, once had climates that supported resin-producing trees,” he said.

The discovery is not only a scientific milestone but also a unique opportunity to study ancient ecosystems.

Researchers are now analyzing the amber to understand whether the forests experienced wildfires or other natural events.

They also hope to find traces of ancient life trapped inside the amber, such as insects or microbes, to piece together a clearer picture of life during the Cretaceous.

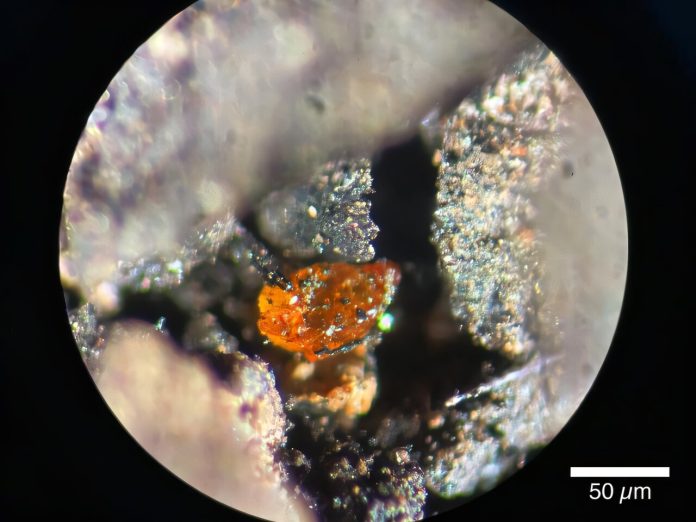

Unlike the large chunks of amber often seen in jewelry, the Antarctic amber is tiny—less than 1 mm in diameter.

The fragments had to be carefully sliced and analyzed using advanced techniques like reflected-light and fluorescence microscopy. Despite their small size, these pieces hold valuable information.

Dr. Gerschel explained that the amber likely came from tree bark and contains microscopic inclusions. Its high quality suggests it was buried near the surface, as deeper burial would have destroyed it under heat and pressure.

One particularly interesting feature is evidence of “pathological resin flow,” which occurs when trees produce extra resin to heal damaged bark. This is a defense mechanism against parasites, wildfires, or infections, creating a chemical barrier to protect the tree.

This discovery adds a new piece to the puzzle of Antarctica’s ancient forests.

“It helps us better understand the swampy, conifer-rich, temperate rainforests that once thrived near the South Pole,” said Gerschel.

The findings shed light on a time when Antarctica was far warmer than today, offering new insights into our planet’s climatic and ecological history.