Researchers have discovered what might be the world’s oldest solar calendar on a stone pillar in Turkey.

This ancient calendar, created 12,000 years ago, is believed to mark a devastating comet strike that had a profound impact on early human civilization.

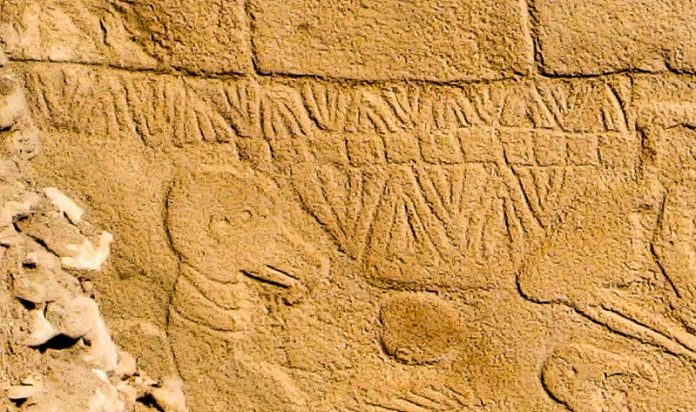

The carvings were found at Göbekli Tepe, an ancient site in southern Turkey known for its impressive temple-like structures adorned with intricate symbols.

Researchers suggest that these markings record an astronomical event that triggered significant changes in human society.

Published in the journal Time and Mind, the study indicates that ancient people at Göbekli Tepe were able to track the sun, moon, and stars.

They created a solar calendar to keep track of time and the changing seasons.

By analyzing V-shaped symbols on the pillars, researchers discovered that each V might represent a single day.

This interpretation led to the identification of a solar calendar with 365 days, composed of 12 lunar months plus 11 extra days.

One special V-shaped symbol around the neck of a bird-like figure is thought to represent the summer solstice constellation. Nearby statues, possibly representing gods, also have similar V-markings on their necks.

The carvings seem to depict both the moon’s phases and the sun’s cycles, making it the earliest known lunisolar calendar, predating others by thousands of years.

Researchers believe these carvings were created to mark the date when a swarm of comet fragments hit Earth around 13,000 years ago, or 10,850 BC.

This comet strike is thought to have caused a mini ice age lasting over 1,200 years, wiping out many large animal species. The aftermath of this event likely led to changes in human lifestyle and agriculture, which are linked to the rise of civilization in West Asia’s fertile crescent.

Another pillar at Göbekli Tepe seems to depict the Taurid meteor stream, believed to be the source of the comet fragments. This stream lasted 27 days and came from the directions of Aquarius and Pisces.

The carvings also suggest that ancient people understood the concept of precession—the slow wobble in Earth’s axis that affects how constellations move across the sky—long before it was documented by the Greek astronomer Hipparchus in 150 BC.

The importance of these carvings to the people of Göbekli Tepe suggests that the comet strike may have led to a new religion or cult that influenced the development of early civilization. This find also supports the theory that Earth’s orbit crosses paths with comet fragments, leading to increased comet strikes, which we experience as meteor showers.

Dr. Martin Sweatman from the University of Edinburgh, who led the research, said, “The inhabitants of Göbekli Tepe were keen sky observers, likely due to the comet strike that devastated their world.

This event may have triggered the development of civilization by inspiring new religious beliefs and advancements in agriculture to survive the cold climate. Their carvings might be the first steps towards writing, created millennia later.”