New research shows that dolphins developed their amazing sonar abilities much earlier than previously thought.

Dr. Rachel Racicot from the Senckenberg Research Institute and her former student, Joyce Sanks from Vanderbilt University, examined the inner ear of the extinct dolphin genus Parapontoporia.

Their study, published in The Anatomical Record, reveals that these ancient dolphins had specialized high-frequency hearing around 5.3 million years ago.

Dolphins and other toothed whales use echolocation, a natural sonar system, to navigate and hunt.

They emit sound waves that bounce off objects and return as echoes, providing information about the distance and size of the objects.

This ability is especially useful in the ocean, where sound travels five times faster than in the air, but visibility is often poor.

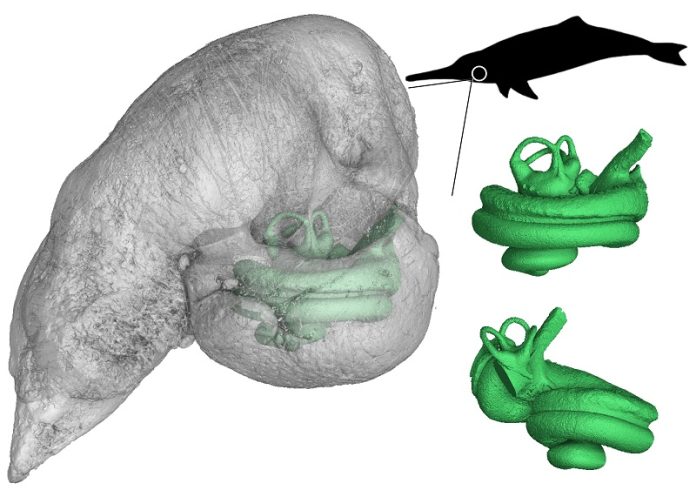

Racicot and Sanks used high-resolution X-ray CT scans to study the inner ear of three Parapontoporia specimens from the San Diego Museum of Natural History.

They created 3D models that showed these dolphins already had narrow-band high-frequency hearing during the Miocene period, about 5 million years ago.

One exciting aspect of their findings is that Parapontoporia dolphins left the ocean to live in rivers. This links them to today’s rare and endangered river dolphins.

River habitats are complex, and the ability to use sonar likely helped these long-snouted dolphins navigate and communicate in their new environment.

The return of cetaceans (whales, dolphins, and porpoises) from land to water about 50 million years ago was a significant evolutionary event.

This change required many adaptations, such as moving their nostrils to the top of their heads and developing streamlined bodies.

Echolocation, which all toothed whales use today, also evolved early in their history.

Understanding how these ancient dolphins adapted to different habitats can help scientists learn more about the evolution of marine mammals. Parapontoporia, a relative of the now-extinct Chinese river dolphin (Lipotes vexillifer), offers insights into the transition from marine to freshwater environments.

The last sighting of the Chinese river dolphin was in 2002, and today, all six species of river dolphins are very rare and threatened with extinction.

Dr. Racicot believes that selective pressure or ecological advantages drove the early and widespread evolution of echolocation in dolphins. River systems are spatially complex, and echolocation would have been a valuable tool for dolphins living in these environments.

Further research into the sensory systems of toothed whales can provide important information about how different habitats influence their hearing and overall evolution.

This study highlights the importance of understanding the past to better protect these incredible animals in the future.