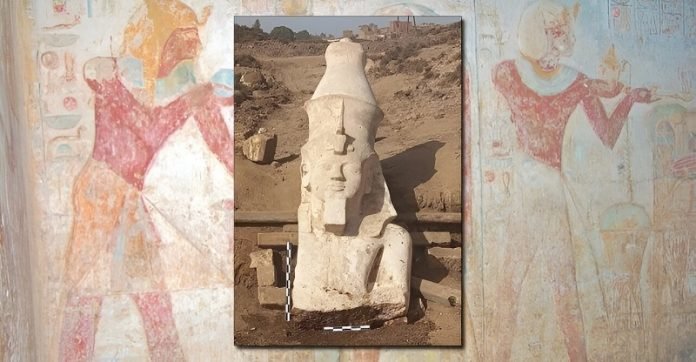

In a thrilling archaeological discovery, a team led by a University of Colorado Boulder researcher has unearthed the top half of a colossal statue of Ramesses II, one of Egypt’s most famous pharaohs.

This find pairs with the statue’s lower half, which was found in 1930, and brings new excitement to the field of Egyptian archaeology.

Yvona Trnka-Amrhein, an assistant professor of classics at CU Boulder, co-led the Egyptian-American team that discovered the statue’s upper portion in the ruins of Hermopolis, an ancient city about 150 miles south of Cairo.

The upper half of the statue measures 12.5 feet and depicts the pharaoh seated with a double crown and a royal cobra atop his head.

The discovery was unexpected according to Trnka-Amrhein, who wasn’t specifically searching for the statue.

The complete statue, once both halves are joined, would stand about 23 feet tall, marking it as one of the significant representations of Ramesses II, who ruled Egypt around 12 centuries BC.

The significance of Ramesses II in both historical and cultural contexts is profound.

He inspired Percy Bysshe Shelley’s poem “Ozymandias” and has been portrayed in modern media such as the movie “The Ten Commandments” and the animated film “The Prince of Egypt.”

The project to unearth this statue began when Trnka-Amrhein, originally focusing on Greek papyri research, was invited by Basem Gehad of the Egyptian Ministry of Tourism and Antiquities to join the excavation at Hermopolis.

This site is notably fertile for Greek papyri and has not seen major excavation work since the 1980s.

The face of the pharaoh, found face-down, was remarkably preserved and still had traces of ancient blue and yellow pigment.

These colors will be analyzed to provide deeper insights into the materials and methods used during Ramesses II’s era.

Gehad, who specializes in paintings from the Greco-Roman period, highlighted the potential insights from the pigment analysis.

The discovery not only excites historians and archaeologists but also poses challenges due to the proximity of the Nile River and the rising water table, which risks damaging the fragile sandstone and limestone artifacts.

Gehad has proposed reuniting the two halves of the statue, which Trnka-Amrhein believes will be approved. The reassembled statue might be displayed at the excavation site or moved to a museum for public viewing and protection.

This discovery is part of ongoing efforts to understand and preserve Egypt’s rich historical legacy, and it also provides an exciting opportunity for CU Boulder graduate students to engage in significant field research.

The team plans to publish their findings later this year, contributing further to our understanding of ancient Egyptian culture and history.