A remarkable discovery in the far northwest of Alaska has given scientists fresh insights into the era when dinosaurs roamed the Earth, connecting continents and thriving in climates we can only imagine today.

This breakthrough comes from an international research team led by paleontologist Anthony Fiorillo, whose findings have recently been unveiled in the Geosciences journal.

Anthony Fiorillo, who embarked on this journey while at Southern Methodist University and now leads the New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science, worked alongside Paul McCarthy from the University of Alaska Fairbanks and a dedicated team, including graduate student Eric Orphys.

This group of scientists has spent over two decades delving into Alaska’s prehistoric climate, sedimentology, and dinosaur paleontology across various regions.

Their latest venture led them to the Nanushuk Formation, a geological marvel dating back about 90 to 100 million years. This time frame is crucial as it marks the potential beginning of the Bering Land Bridge, a natural bridge between Asia and North America.

Fiorillo and his team were driven by the desire to understand the dynamics of this bridge—how it was used by ancient creatures and the conditions they faced.

The backdrop for this research is the Nanushuk Formation, stretching across the central and western North Slope of Alaska. This formation, aged between 94 million to 113 million years, provides a window into the mid-Cretaceous Period.

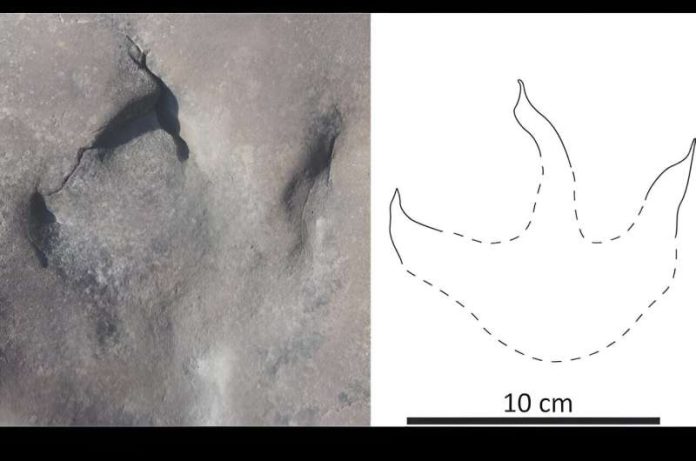

The team’s fieldwork from 2015 to 2017 focused on Coke Basin, revealing around 75 dinosaur tracks and evidence of a vibrant ecosystem, including fossilized plants and tree stumps, indicating a riverine or delta environment thriving millions of years ago.

This discovery paints a picture of an ancient world, where one could literally walk through a prehistoric forest, surrounded by large trees, smaller plants, and the marks left by dinosaurs.

Fiorillo’s excitement is palpable as he describes the landscape filled with dinosaur footprints, fossilized feces, and the sheer richness of life that once existed.

Their research sheds light on the types of dinosaurs that dominated the area. Interestingly, bipedal plant-eating dinosaurs were the most prevalent, making up 59% of the total tracks found.

This contrasts with the smaller percentages of four-legged plant eaters, birds, and primarily carnivorous bipedal dinosaurs.

The significant number of bird tracks aligns with the notion that the warm paleoclimate of the time was conducive to bird life, much like the Arctic during the warm months today.

Another intriguing aspect of their findings is the climate data derived from carbon isotope analysis of wood samples.

The analysis suggests that the region received about 70 inches of precipitation annually, pointing to a climate comparable to modern-day Miami, with high rainfall and warmer temperatures. This is particularly notable given that the site was further north during the mid-Cretaceous than it is today.

The work of Fiorillo, McCarthy, and their team not only adds a new chapter to our understanding of dinosaur migration and climate but also hints at the vast amount of research still to be uncovered.

Their findings contribute to the broader narrative of Earth’s history, offering insights into the climatic conditions of the past and how these might inform our understanding of the present and future climate challenges.

The research findings can be found in Geosciences.

Copyright © 2024 Knowridge Science Report. All rights reserved.