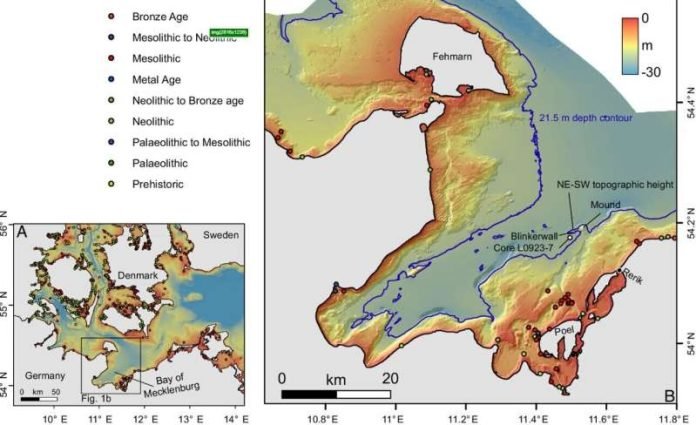

In the fall of 2021, a remarkable discovery was made at the bottom of the Mecklenburg Bight, near Rerik, about 10 kilometers off the coast.

Geologists stumbled upon a long, unusual row of stones nearly a kilometer in length, resting 21 meters deep in the Baltic Sea. The arrangement of approximately 1,500 stones seemed too orderly to have formed naturally, sparking intrigue among researchers.

A diverse team of experts embarked on a quest to uncover the origins and purpose of this stone structure.

Their findings, published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, suggest that Stone Age hunter-gatherers constructed this wall around 11,000 years ago as a hunting tool for reindeer.

This revelation marks the first discovery of a Stone Age hunting structure in the Baltic Sea region.

The initial discovery happened somewhat by accident. Researchers and students from Kiel University (CAU) were examining the sea floor for manganese crusts when they came across the stone row.

The structure’s precise alignment and connection of several large boulders with smaller stones intrigued the team. They reported their find to the local authority responsible for cultural heritage preservation, which led to further investigations.

The stone wall is positioned on a ridge made of basal till, a type of glacial deposit, suggesting that it was constructed before the sea levels rose after the last ice age, around 8,500 years ago. This period saw the flooding of vast landscapes that had previously been dry.

To delve deeper into this mystery, scientists employed modern geophysical methods, creating a detailed 3D model of the wall and reconstructing the ancient landscape.

Divers explored the structure, while sediment samples from a nearby basin provided clues about the wall’s construction timeline.

The researchers concluded that the stone wall’s creation by natural forces or for modern purposes, such as submarine cable laying, was highly unlikely. The deliberate arrangement of stones indicated a human-made structure, designed for a specific purpose.

The theory is that during a time when Europe’s northern population was incredibly sparse, hunter-gatherers used the wall to direct migrating reindeer herds into traps for easier hunting.

Comparable strategies have been identified in other parts of the world, such as the stone walls and hunting blinds found at the bottom of Lake Huron, used for hunting caribou.

Given that the last reindeer herds vanished from the region about 11,000 years ago due to climate change and the spread of forests, the wall likely dates from this period, making it the oldest human-made structure discovered in the Baltic Sea.

While numerous archaeological sites from later periods have been found in shallower waters along the coast, this discovery provides a unique insight into the life and hunting practices of early Stone Age people.

The research team plans to conduct more detailed investigations of the stone wall and the surrounding seabed, including further diving campaigns and the use of luminescence dating to pinpoint the construction date more accurately.

They also aim to explore other similar structures in the area, hoping to piece together a clearer picture of the region’s ancient inhabitants and their way of life.

This ongoing research not only sheds light on the ingenuity of early human societies but also enriches our understanding of prehistoric life in the Baltic Sea region.

The research findings can be found in PNAS.

Copyright © 2024 Knowridge Science Report. All rights reserved.