In a recent study led by Catherine Neish, a researcher with a background in studying planets and life in space, it was discovered that the ocean hidden beneath the icy surface of Titan, Saturn’s largest moon, probably can’t support life.

This finding dims the hope of finding living organisms in the far-off corners of our solar system, especially around the giant planets like Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus, and Neptune.

Neish, who teaches about Earth and its place in the universe, expressed disappointment, noting that the scientific world had been buzzing with excitement at the prospect of discovering life on icy moons that orbit these distant giants.

These moons, including Titan, are fascinating because they hold vast oceans beneath their frozen exteriors, much larger than all of Earth’s oceans combined. Since water is essential for life as we know it, these watery worlds have drawn a lot of attention from those hunting for alien life.

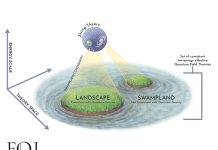

The study, which Neish and her team published, aimed to figure out how much organic material from Titan’s surface could mix into its deep ocean.

They used data from space rocks crashing into Titan over time, melting parts of its icy shell and creating a mix with surface materials. This mixture, heavier than the surrounding ice, could potentially sink all the way down to the hidden ocean below.

By calculating the frequency of these cosmic collisions, the team estimated how much of this organic-laden water could seep into Titan’s ocean.

However, they found that only a small amount of organic material, about as much as a large elephant’s weight in the simplest amino acid each year, could make this journey.

This is far too little to support life in an ocean more than twelve times the size of ours, particularly because life requires not just water but also significant amounts of carbon.

This revelation is especially sobering when considering Titan is one of the most organic-rich moons we know of. If Titan’s ocean isn’t welcoming to life, the chances are even slimmer for other icy worlds with less organic material on their surfaces.

Despite these disheartening findings about Titan’s ocean, Neish remains involved in the exciting Dragonfly mission. This NASA project plans to send a drone-like spacecraft to Titan in 2028 to explore its surface directly.

Unlike telescopes, which struggle to see through Titan’s thick, murky atmosphere, Dragonfly will touch down and analyze the moon’s surface materials up close, shedding light on the complex chemistry of organics and water.

The only previous mission to land on Titan, the Cassini–Huygens mission in 2005, provided invaluable data, but Dragonfly will go further, seeking out areas where water and organics have mixed due to impacts.

This could reveal new insights into prebiotic chemistry—the chemical processes that precede the emergence of life.

Neish had concerns that her study’s findings might cast a shadow over the Dragonfly mission. Instead, it has opened up new avenues of inquiry about the surface chemistry of Titan.

By identifying areas where organic compounds and water from impact melts have mixed but not sunk deep into the ice, Dragonfly can target these spots to study possible prebiotic reactions.

This could enhance our understanding of how life might arise on different worlds, despite the inhospitable conditions in Titan’s ocean.

The research findings can be found in Astrobiology.

Copyright © 2024 Knowridge Science Report. All rights reserved.