In a groundbreaking discovery, archaeologists from Freie Universität Berlin, together with an international team, have unearthed ancient fortified settlements in Siberia that date back 8,000 years.

These structures, built by hunter-gatherers, are challenging long-held views about the evolution of early human societies.

The study, titled “The World’s Oldest-Known Promontory Fort: Amnya and the Acceleration of Hunter-Gatherer Diversity in Siberia 8000 Years Ago,” was recently published in the journal Antiquity.

This research is reshaping our understanding of how early humans lived, showing that complex societies didn’t necessarily start with farming communities.

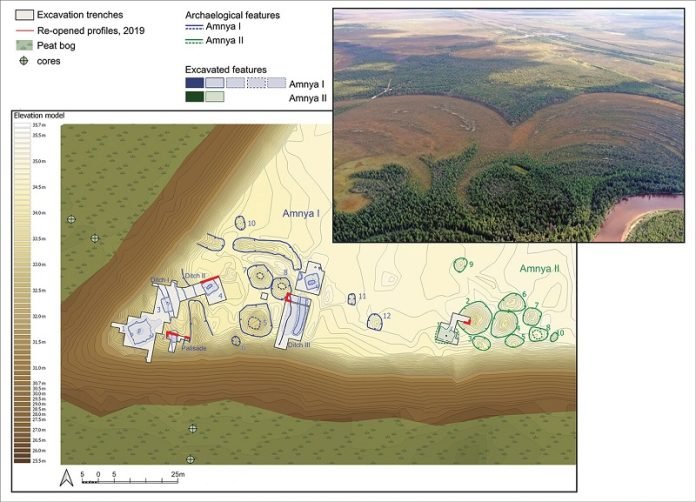

Led by Professor Henny Piezonka and Dr. Natalia Chairkina, the team focused on the Amnya settlement, now recognized as the northernmost Stone Age fort in Eurasia.

Fieldwork conducted in 2019 revealed that the people who lived there led a surprisingly sophisticated life, contrary to what was previously thought about hunter-gatherer societies.

Archaeologist Tanja Schreiber explains that detailed examinations at Amnya, including radiocarbon dating and palaeobotanical studies, confirmed its age and status as the world’s oldest-known fort.

The inhabitants of this region, known for its abundant taiga environment, had a rich lifestyle, hunting elk and reindeer and catching fish from the Amnya River.

They even made elaborately decorated pottery to store surplus fish oil and meat.

This discovery is significant because it challenges the notion that permanent settlements with defensive structures began only with the advent of agriculture.

Approximately ten such Stone Age fortified sites have been found, all featuring pit houses and surrounded by earthen walls and wooden palisades. These structures indicate that these hunter-gatherers possessed advanced architectural and defensive skills.

Moreover, these findings, along with others like Gobekli Tepe in Anatolia, are prompting a reevaluation of the idea that societies evolved in a linear fashion from simple to complex.

It’s becoming clear that various communities, from the Korean peninsula to Scandinavia, developed large settlements based on natural resources like fish.

In Siberia, the abundance of resources such as fish runs and migrating herds likely played a crucial role in the development of these fortified settlements.

Overlooking rivers, these forts were strategically placed to control productive fishing spots.

The presence of these structures suggests that competition and conflict were part of life in these societies, contradicting previous beliefs that such dynamics were absent among hunter-gatherers.

The Siberian forts demonstrate that there were diverse pathways to developing complex societal organizations, as evidenced by the emergence of monumental constructions like these forts. They also highlight the importance of local environmental conditions in shaping human societies.

In essence, this discovery not only provides a fascinating glimpse into our ancient past but also forces us to rethink our assumptions about the progression of human civilization.

The existence of these ancient Siberian fortresses reveals that complexity in human societies could arise in various forms, much earlier than previously believed.