A fascinating new study reveals surprising details about the eating habits of some of the largest carnivorous dinosaurs that roamed North America millions of years ago.

Conducted by Roberto Lei from the Università degli Studi di Modena e Reggio Emilia and his team, the research focuses on the bite marks left on the bones of huge, long-necked dinosaurs like Diplodocus and Brontosaurus.

Their findings, published in the journal PeerJ, offer a unique glimpse into the lives of these prehistoric giants.

For a long time, scientists believed that the massive tyrannosaurs, known for their ferocious reputation, were primarily responsible for the bite marks found on dinosaur bones.

However, Lei and his colleagues dug deeper to understand the role of other large carnivorous dinosaurs in these ancient ecosystems.

They examined an impressive number of fossil records, focusing on 68 sauropod bones from the Upper Jurassic period, about 150 million years ago, from the Morrison Formation in the U.S.

Their study revealed clear bite traces from theropod dinosaurs on these bones. Interestingly, the research indicates that while bite marks on large sauropods were less common in areas dominated by tyrannosaurs, they were surprisingly abundant in the Morrison Formation.

A key observation made by the researchers was that none of the bite marks showed signs of healing. This suggests that the bites were either part of a fatal attack or, more likely, were the result of scavenging behavior by theropods feeding on already dead sauropods.

In addition to examining bones, the team also studied the wear and tear on the teeth of theropod dinosaurs from the Morrison Formation.

They discovered that these carnivores often bit into bones, a finding that was previously believed to be more typical of tyrannosaurs. This similarity in feeding patterns between the Morrison Formation theropods and the tyrannosaurs was an unexpected discovery.

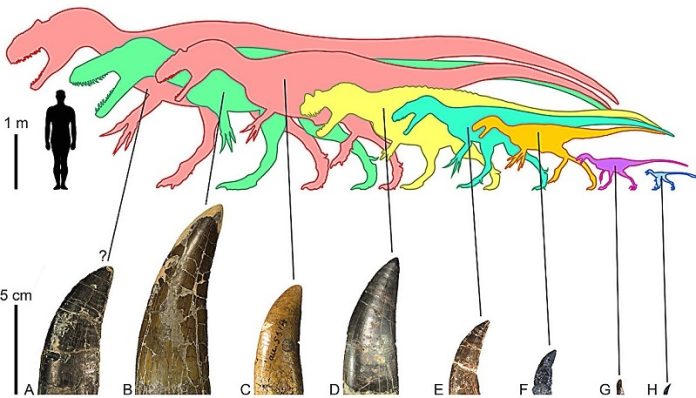

However, pinpointing which specific theropod species made the bite marks remains challenging. The Morrison Formation was home to multiple large carnivores, including well-known dinosaurs like Allosaurus and Ceratosaurus, making it difficult to attribute the bite marks to a particular predator.

Dr. David Hone of Queen Mary University of London, the corresponding author of the study, emphasizes the importance of this research in understanding the relationships between dinosaurs during the Jurassic period.

The study provides new insights into the behavior of these ancient animals and how they interacted within their ecosystems.

This research not only sheds light on the predator-prey dynamics of the late Jurassic period but also raises exciting questions about the complex web of life during that era.

By focusing on bite and tooth marks, the authors have opened a new chapter in paleontology, offering a vivid picture of the interactions between some of Earth’s largest-ever predators and their prey.