Thousands of years ago, groups of people living in northern Europe, belonging to the Magdalenian culture, had a unique way of honoring their dead: they ate them.

This wasn’t due to scarcity of food or out of necessity but seemed to be a deliberate, ritualistic practice, as per recent findings published in Quaternary Science Reviews.

The Intrigue of Gough’s Cave

Located in the picturesque Cheddar Gorge of south-eastern England, Gough’s Cave holds whispers of the ancient Magdalenian people’s life and death practices.

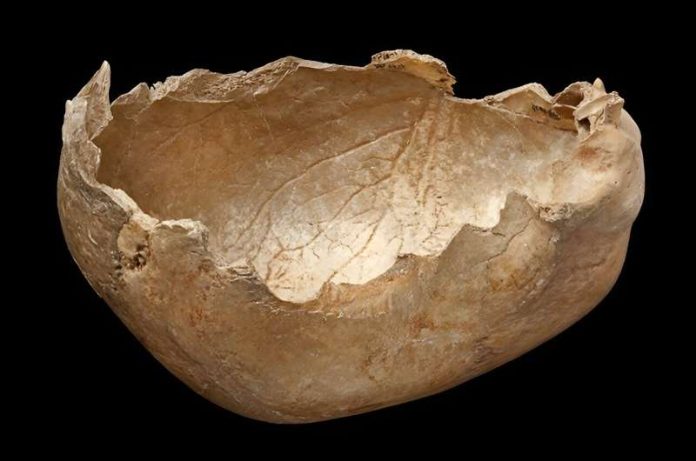

Around 15,000 years ago, they used to consume their deceased and even utilized their bones to create tools or items, such as skull cups.

Archaeological finds and cut marks on the bones confirm that this was a deliberate act, but was it a mere isolated occurrence or a widespread practice?

Cultural Cannibalism across Europe

The recent study led by Dr. Silvia Bello, a specialist in human behavior evolution at the Natural History Museum, points towards the latter.

Magdalenian remains, showing evident signs of cannibalism, have been discovered not just in Gough’s Cave but also across various sites in northern and western Europe.

This widespread practice of consuming the dead within the same cultural and temporal context indicates that it was a collective funerary behavior, rather than an act of survival during harsh times.

Bello explains, “We interpret the evidence that cannibalism was practiced on multiple occasions across north-western Europe over a short period of time, as this practice was part of a diffuse funerary behavior among Magdalenian groups.”

The decision to consume their own wasn’t rooted in nutritional needs; people of that era had access to other food resources, and their elaborate methods of handling the human remains suggest a deeper, symbolic significance.

For example, at Gough’s Cave, a human skull was meticulously shaped into a cup after its flesh had been removed, indicating a ritualistic aspect to the practice.

A Shift in Funerary Practices: Why?

Within a relatively short timeframe, a noticeable shift occurred.

The cannibalistic practices of the Magdalenian people dwindled, making way for burial practices more recognizable to modern humans, performed by a different culture known as the Epigravettian, which was mainly concentrated in south and eastern Europe.

The puzzling transition raises a significant query: Did the Magdalenian people evolve their funerary practices or were they replaced by the Epigravettian?

Dr. William Marsh from the Natural History Museum, delving into this mystery, unearthed evidence suggesting that two genetically distinct populations were involved.

The GoyetQ2 genetic group, associated with the Magdalenian and their cannibalistic practices, seems to have been supplanted by the Villabruna genetic group, linked to the Epigravettian and their burial customs.

According to Marsh, “The Magdalenian associated ancestry and funerary behavior is replaced by Epigravettian associated ancestry and funerary behavior, indicative of population replacement as Epigravettian groups migrated into north-western Europe.”

Lingering Questions and Continued Exploration

Even as this discovery unveils aspects of our ancient ancestors’ lives and practices, numerous questions linger. Who were the individuals chosen to be consumed, and why? Were they kin or outsiders?

As researchers delve deeper, exploring the nexus between ancient funerary practices, migration, and cultural evolution, we’re given a glimpse into the rich tapestry of human history, showcasing our species’ diversity and complexity in dealing with life, death, and remembrance.

In unearthing the past, Dr. Bello, Dr. Marsh, and their colleagues beckon us to contemplate the myriad ways our ancestors understood and interacted with the phenomena of death, unearthing not just bones, but stories and rituals from the fog of prehistory.

The practices of our ancient ancestors, however alien they may seem now, form a crucial chapter in the narrative of human cultural evolution and diversification.

The research findings can be found in Quaternary Science Reviews.