Palaeontologists have discovered remarkable new evidence that pterosaurs, the flying relatives of dinosaurs, were able to control the colour of their feathers using melanin pigments.

The study, published in the journal Nature, was led by University College Cork (UCC) palaeontologists Dr Aude Cincotta and Prof. Maria McNamara and Dr Pascal Godefroit from the Royal Belgian Institute of Natural Sciences, with an international team of scientists from Brazil and Belgium.

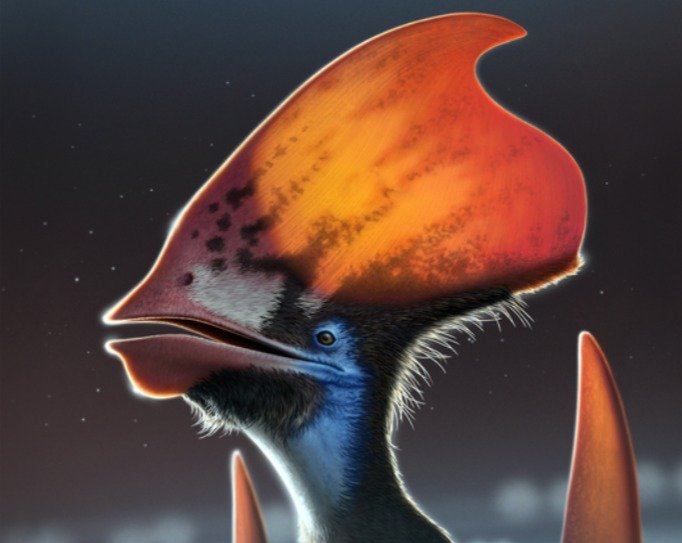

The new study is based on analyses of a new 115 million year old fossilized headcrest of the pterosaur Tupandactylus imperator from north-eastern Brazil.

Pterosaurs lived side by side with dinosaurs, 230 to 66 million years ago.

This species of pterosaur is famous for its bizarre huge headcrest.

The team discovered that the bottom of the crest had a fuzzy rim of feathers, with short wiry hair-like feathers and fluffy branched feathers.

“We didn’t expect to see this at all”, said Dr Cincotta. “For decades palaeontologists have argued about whether pterosaurs had feathers.

The feathers in our specimen close off that debate for good as they are very clearly branched all the way along their length, just like birds today”.

The team then studied the feathers with high-powered electron microscopes and found preserved melanosomes – granules of the pigment melanin. Unexpectedly, the new study shows that the melanosomes in different feather types have different shapes.

“In birds today, feather colour is strongly linked to melanosome shape.” said Prof. McNamara.

“Since the pterosaur feather types had different melanosome shapes, these animals must have had the genetic machinery to control the colours of their feathers.

This feature is essential for colour patterning and shows that coloration was a critical feature of even the very earliest feathers.”

Thanks to the collective efforts of the Belgian and Brazilian scientists and authorities working with a private donor, the remarkable specimen has been repatriated to Brazil.

“It is so important that scientifically important fossils such as this are returned to their countries of origin and safely conserved for posterity” said Dr Godefroit.

“These fossils can then be made available to scientists for further study and can inspire future generations of scientists through public exhibitions that celebrate our natural heritage”.

Source: University College Cork.