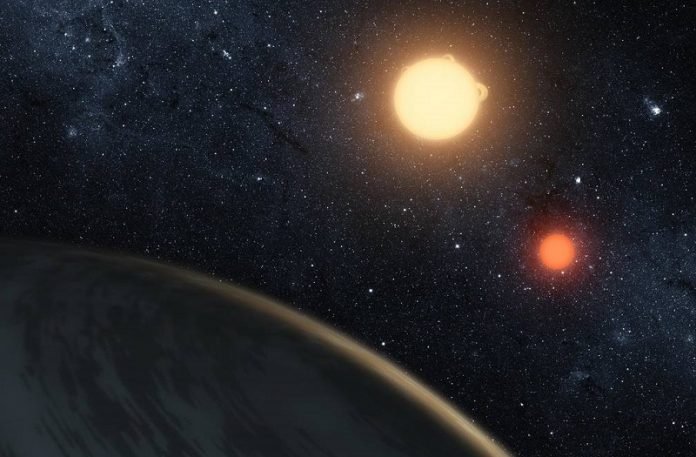

Remember that iconic scene in Star Wars, where a young Skywalker steps out onto the surface of Tatooine and watches the setting of two suns?

As it turns out, this may be what it is like for lifeforms on the exoplanet known as Kepler-16, a rocky planet that orbits in a binary star system.

Originally discovered by NASA’s Kepler mission, an international team of astronomers recently confirmed that this planet orbits two stars at once – what is known as a circumbinary planet.

The international team, led by Professor Amaury Triaud of the University of Birmingham, comprises members of the BEBOP collaboration.

This observation campaign began in 2013 and relied on telescopes from around the world to conduct radial velocity surveys for circumbinary planets.

The team’s research is published in Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society.

The planet, known as Kepler-16b, is located approximately 245 light-years from Earth and orbits its binary stars with a period of 228.8 days.

Like Tatooine, life forms on this planet would look up into the sky and see two suns rising and setting. However, the planet orbits outside its two stars’ “habitable zone,” meaning that conditions on the surface are likely very cold. It was discovered in 2011 by Kepler using the Transit Method (aka. Transit Photometry).

For this method, astronomers observe stars for periodic dips in brightness that indicate the presence of orbiting planets.

Astronomers also rely on this method because it effectively establishes constraints on an exoplanet’s size.

For the sake of their study, the team relied on the SOPHIE echelle spectrograph on the 193-cm telescope at the Observatoire de Haute-Provence to perform Radial Velocity (aka. Doppler Spectroscopy) measurements on the system.

This method consists of observing stars for signs of “wobble,” which indicates that gravitational forces are acting on them (caused by one or more planets). As co-author Dr. Alexandre Santerne (a researcher from Aix-Marseille University) explained in a Royal Astronomical Society press release:

“Kepler-16b was first discovered 10 years ago by NASA’s Kepler satellite using the transit method.

This system was the most unexpected discovery made by Kepler. We chose to turn our telescope to Kepler-16 to demonstrate the validity of our radial-velocity methods.”

Their measurements confirmed that Kepler-16b orbits both stars (which orbit each other), a finding that may help resolve an open question about binary star systems.

According to the most widely-accepted model of planet formation, planets are believed to form within a disk of dust and gas surrounding young stars – aka. a protoplanetary disk.

This presents some difficulties where binary systems are concerned, as the model predicts that the gravitational forces might interfere with planet formation.

In recent years, the discovery and statistical significance of “Hot Jupiters” have also raised questions for astronomers.

According to the protoplanetary disk model, gas giants cannot form this close to their stars due to insufficient mass and excessive heat.

The only possible explanation, according to astronomers, is that planets (while they are still in the process of formation) migrate within the disk as a result of gravitational interactions with other bodies.

These findings indicate that disc-driven migration is a viable process and a relatively common occurrence. Said Prof. Triaud:

“Using this standard explanation it is difficult to understand how circumbinary planets can exist. That’s because the presence of two stars interferes with the protoplanetary disc, and this prevents dust from agglomerating into planets, a process called accretion.

“The planet may have formed far from the two stars, where their influence is weaker, and then moved inwards in a process called disc-driven migration – or, alternatively, we may find we need to revise our understanding of the process of planetary accretion.”

The detection of Kepler-16b using a ground-based telescope and the Radial Velocity Method was also significant.

Essentially, it demonstrated that it is possible to detect circumbinary planets using more traditional methods with greater efficiency and lower costs than space-based observatories. With this success under their belts, the team plans to continue searching for previously unknown circumbinary planets and help answer questions about planetary formation.

As co-author Dr. Isabelle Boisse, the scientist in charge of the SOPHIE instrument at Aix-Marseille University, summarized:

“Our discovery shows how ground-based telescopes remain entirely relevant to modern exoplanet research and can be used for exciting new projects.

Having shown we can detect Kepler-16b. We will now analyze data taken on many other binary star systems and search for new circumbinary planets.”

Written by Matt Williams.

Source: Universe Today.