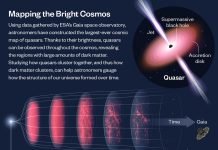

Scientists have obtained the first image of a black hole, using Event Horizon Telescope observations of the center of the galaxy M87.

The image shows a bright ring formed as light bends in the intense gravity around a black hole that is 6.5 billion times more massive than the Sun.

Honoring a feat that was once considered impossible, Science has named the Event Horizon Telescope’s image of a supermassive black hole as its 2019 Breakthrough of the Year.

The image reveals one of the darkest and most elusive phenomena in the known universe.

“This was a great year for science, but what could be more wondrous than actually seeing a black hole?

It sounds like magic, but it was really an astonishing feat of teamwork and technology,” says Tim Appenzeller, Science’s news editor. Black holes are immensely dense cosmic objects with gravity so strong that they capture and consume everything surrounding them, including light.

Since they reflect no light, black holes often hide in plain sight, perfectly camouflaged against the inky black of the void.

However, by imaging the cloud of hot, brightly glowing gas that surrounds it, the EHT team of more than 200 scientists was able to capture the silhouette of the super massive black hole that lies at the center of Messier 87 (M87), a galaxy nearly 55 million light-years from Earth.

While massive–M87’s black hole weighs as much as 6.5 billion suns–it is small by galactic standards at roughly the size of our Solar System. “I’m still kind of stunned,” said Roger Blandford, a Stanford University astrophysicist.

“I don’t think any of us imagined the iconic image that was produced.”

The historic image of the distant stellar object also captured the minds and imaginations of people world-wide – from front-page international news stories to internet memes – and quickly became the most downloaded image in the history of the National Science Foundation’s website.

Currently, plans are underway for more observations with even greater resolution; “this year’s triumph is the beginning, not the culmination, of this research project, said Blandford.