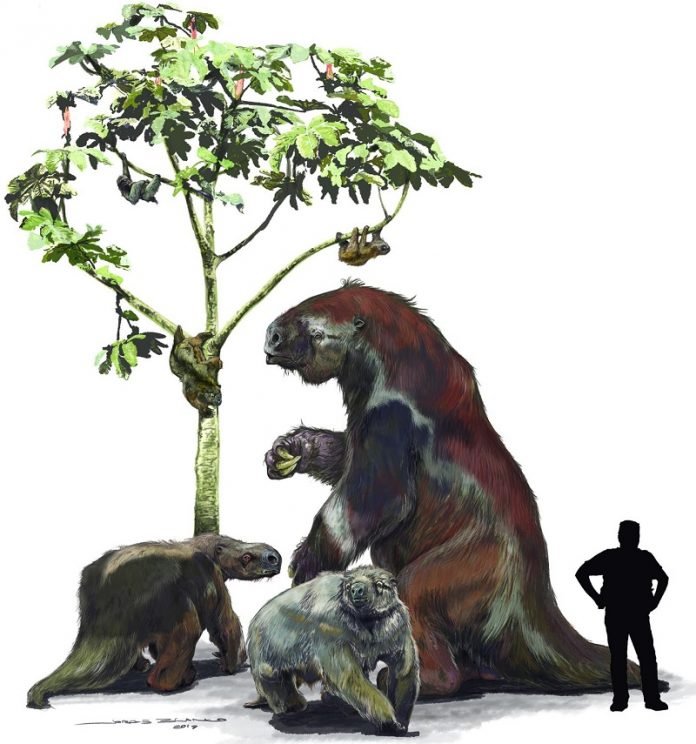

Scientists have solved the evolutionary puzzle of how sloths went from enormous ground-dwelling giants to the small, famously-laidback tree-climbers of the modern day.

The study, by an international team of researchers led by academics at the University of York, challenges decades of scientific opinion concerning the evolutionary relationships of tree sloths and their extinct kin.

The two living types of sloth – two and three toed – seem remarkably similar, but the new research published in Nature Ecology and Evolution estimates they last shared a common ancestor more than 30 million years ago.

The researchers unexpectedly discovered that the three-toed sloth is related to two giant ground sloths – the elephant-sized Megatherium and the pony-sized Megalonyx, which last roamed the earth around 10,000 years ago.

The researchers used cutting-edge techniques to extract ancient protein sequences from the fossilized bones of extinct sloths held in the collections of the American Museum of Natural History in order to map their relationship to living species of sloth.

Protein analysis allowed researchers to analyze fossilized sloth bones that were between 120,000 and 400,000 years old.

Lead author of the study, Samantha Presslee, a PhD student in the Department of Archaeology at the University of York, said: “Scientists have long been perplexed by the fact we used to have huge ground sloths and have ended up with modern, small, tree-dwelling ones.

“Previous analysis of the sloth family tree has been done by looking at the anatomy of extinct sloths from often-fragmented skeletons in the fossil record, but protein analysis gives us quite a different picture.

Structural proteins in bone such as collagen encode information that can last up to around 3.8 million years.”

The study is published at the same time as another piece of related research is reported in the journal Current Biology.

The second study analysed ancient DNA found in well-preserved fossilised sloth bones and, while the two research teams used different molecular methods, they produced the same results, verifying the family tree findings of both studies.

While in this case scientists were able to use both methods to examine the evolutionary history of the sloth, protein analysis has the potential to take researchers further back into the evolutionary past of a wider range of animals than ever before.

Dr Kirsty Penkman from the Department of Chemistry at the University of York, who was also involved in the protein study, said: “We now have the potential to extract and interpret protein evidence from a wide range of extinct species well beyond the current reach of ancient DNA, which is a relatively fragile molecule.

“Looking at DNA offers amazing insights, particularly into remains that have been preserved in permafrost, but this obviously limits the range of species you can look at.

This method allows scientists to go back into deeper time and look at species that lived and died in warmer climates.”

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41559-019-0909-z.