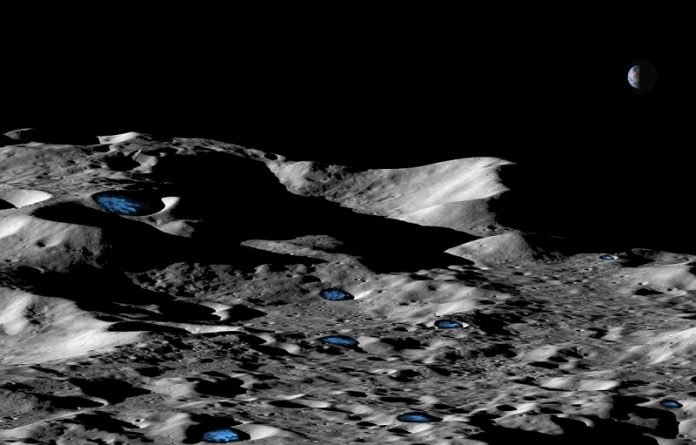

There may be enough water to sustain a future lunar settlement.

The polar regions of the moon may contain significantly more water ice than previously thought, according to new research by UCLA space scientists.

The study, published July 22 in Nature Geoscience, points to the existence of previously undetected thick ice deposits on the moon. It was led by Lior Rubanenko, a UCLA graduate student.

Over the past two decades, observations from telescopes and spacecraft have found glacier-like water ice deposits near Mercury’s poles, but none had been seen on the moon.

The difference raised what is now one of the most important questions in planetary science: Why, despite their similar surface conditions, does the moon have so much less ice than Mercury?

“The simple answer is that the moon has lots of ice — it’s just buried below the surface,” said David Paige, a UCLA professor of planetary science and a co-author of the study.

Jaahnavee Venkatraman, a recent UCLA graduate and the paper’s second author, said the new observations suggest that there may be a reservoir of frozen water sufficiently massive to sustain a future human settlement on the moon.

Unlike the Earth, the spin axes of the moon and Mercury are very small.

As a result, craters and other depressions located near the poles on both bodies never see the sun, which makes them among the coldest places in our solar system.

For decades it has been postulated these permanently shadowed regions are so cold that any ice trapped within them could survive for billions of years.

Radar observations of Mercury conducted two decades ago revealed thick, pure ice deposits.

In 2014, NASA’s Messenger spacecraft imaged the ice deposits, and scientists determined that they were up to 50 meters thick and, at least in part, relatively fresh — between 10 million and 100 million years old.

Parallel investigations conducted on the moon, whose polar thermal environments are very similar to those of Mercury, found only patchy, shallow ice deposits.

Paige said that difference was the impetus for the UCLA study.

The airless surfaces of Mercury and the moon are scarred by myriad depressions called impact craters. The craters, which form when meteorites impact the surface, can generally be divided into two groups.

Smaller, less energetic impactors form smaller simple craters: depressions that are held together by the strength of the surface dust layer, or regolith. More energetic impactors form larger complex craters, cavities so large that their steep walls collapse under their own weight.

Simple craters tend to be more circular and symmetric than complex craters, a fact the UCLA scientists exploited to estimate the thickness of ice trapped within them.

Using data from Messenger and NASA’s Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter spacecraft, they measured approximately 15,000 simple craters with diameters ranging from 2.5 to 15 kilometers (about 1.5 to 9 miles) on Mercury and the moon.

They found that craters become up to 10% shallower near the north pole of Mercury and the south pole of the moon than the craters at lower latitudes on both bodies — but they also found that craters at the north pole of the moon don’t fit that pattern. (Messenger didn’t take measurements at the south pole of Mercury.)

“We found that shallow craters tend to be located in areas where surface ice was previously detected near the south pole of the moon,” Rubanenko said.

According to the study, the most probable explanation for those shallower craters is the accumulation of previously undetected thick ice deposits.

Supporting that conclusion are the researchers’ findings that the slopes of the craters that face the poles are slightly shallower than their equator-facing slopes, and that craters are significantly shallower in areas where ice is less likely to convert directly from its solid form to vapor because of Mercury’s orbit around the sun.

Additionally, unlike Mercury, where the ice has been shown by radar telescope observations to be nearly pure, the deposits detected on the moon are most likely mixed with the regolith, possibly in a layered formation.

This might imply that the deposits on the moon are older than the more pristine deposits on Mercury.

Written by Lisa Garibay.