North Carolina State University researchers have developed the first portable technology that can test for cyanotoxins in water.

The device can be used to detect four common types of cyanotoxins, including two for which the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) recently finalized recreational water quality criteria.

Cyanotoxins are toxic substances produced by cyanobacteria.

At high enough levels, cyanotoxins can cause health effects ranging from headache and vomiting to respiratory paralysis and death.

The new technology can detect four common types of cyanotoxins: anatoxin-a, cylindrospermopsin, nodularin and microcystin-LR.

One reason the portable technology may be particularly useful is that EPA finalized water quality criteria this month for both microcystin-LR and cylindrospermopsin in recreational waters.

“Our technology is capable of detecting these toxins at the levels EPA laid out in its water quality criteria,” says Qingshan Wei, an assistant professor of chemical and biomolecular engineering at NC State and corresponding author of a paper on the work.

“However, it’s important to note that our technology is not yet capable of detecting these cyanotoxins at levels as low as the World Health Organization’s drinking water limit.

So, while this is a useful environmental monitoring tool, and can be used to assess recreational water quality, it is not yet viable for assessing drinking water safety.”

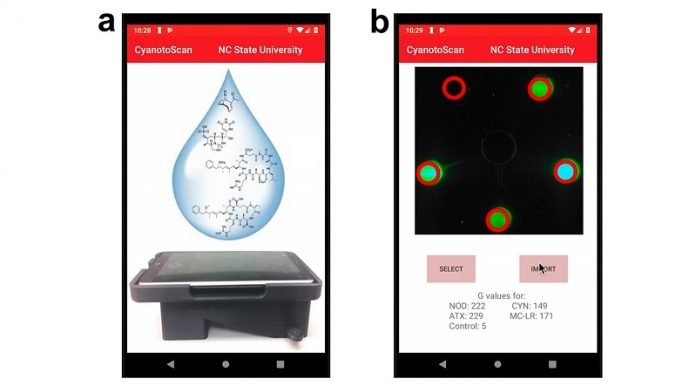

To test for cyanotoxins, users place a drop of water on a customized chip developed in Wei’s lab, then insert it into a reader device, also developed in Wei’s lab, which connects to a smartphone.

The technology can detect and measuring organic molecules associated with the four cyanotoxins, ultimately providing the user’s smartphone with the cyanotoxin levels found in the relevant water sample. The entire process takes five minutes.

“The reader cost us less than $70 to make, each chip cost less than a dollar, and we could make both even less expensive if we scaled up production,” says Zheng Li, a postdoctoral researcher at NC State and first author of the paper.

“Our current focus with this technology is to make it more sensitive, so that it can be used to monitor drinking water safety,” Wei says.

“More broadly, we believe the technology could be modified to look for molecular markers associated with other contaminants.”

Written by Matt Shipman.