Deep down lies the core of the Earth, followed by the Earth’s mantle. The Earth’s crust begins 35 kilometers below the surface.

The huge magnetic field which surrounds the Earth, protecting it from radiation and charged particles from space—and which many animals even use for orientation purposes—is changing constantly, which is why geoscientists keep it constantly under surveillance.

The old well-known sources of the Earth’s magnetic field are the Earth’s core—down to 6,000 kilometers deep down inside the Earth—and the Earth’s crust: in other words, the ground we stand on.

The Earth’s mantle, on the other hand, stretching from 35 to 2,900 kilometers below the Earth’s surface, has so far largely been regarded as “magnetically dead.”

An international team of researchers from Germany, France, Denmark and the U.S. has now demonstrated that a form of iron oxide, hematite, can retain its magnetic properties even deep down in the Earth’s mantle.

This occurs in relatively cold tectonic plates, called slabs, which are found especially beneath the western Pacific Ocean.

“This new knowledge about the Earth’s mantle and the strongly magnetic region in the western Pacific could throw new light on any observations of the Earth’s magnetic field,” says mineral physicist and first author Dr. Ilya Kupenko from the University of Münster (Germany).

The new findings could, for example, be relevant for any future observations of the magnetic anomalies on the Earth and on other planets such as Mars.

This is because Mars has no longer a dynamo and thus no source enabling a strong magnetic field originating from the core to be built up such as that on Earth.

It might, therefore, now be worth taking a more detailed look on its mantle.

The study has been published in Nature.

Background and methods used

Deep in the metallic core of the Earth, it is liquid iron alloy that triggers electrical flows. In the outermost crust of the Earth, rocks cause magnetic signal.

In the deeper regions of the Earth’s interior, however, it was believed that the rocks lose their magnetic properties due to the very high temperatures and pressures.

The researchers now took a closer look at the main potential sources for magnetism in the Earth’s mantle: iron oxides, which have a high critical temperature—i.e. the temperature above which material is no longer magnetic.

In the Earth’s mantle, iron oxides occur in slabs that are buried from the Earth’s crust further into the mantle, as a result of tectonic shifts, a process called subduction.

They can reach a depth within the Earth’s interior of between 410 and 660 kilometres—the so-called transition zone between the upper and the lower mantle of the Earth.

Previously, however, no one had succeeded in measuring the magnetic properties of the iron oxides at the extreme conditions of pressure and temperature found in this region.

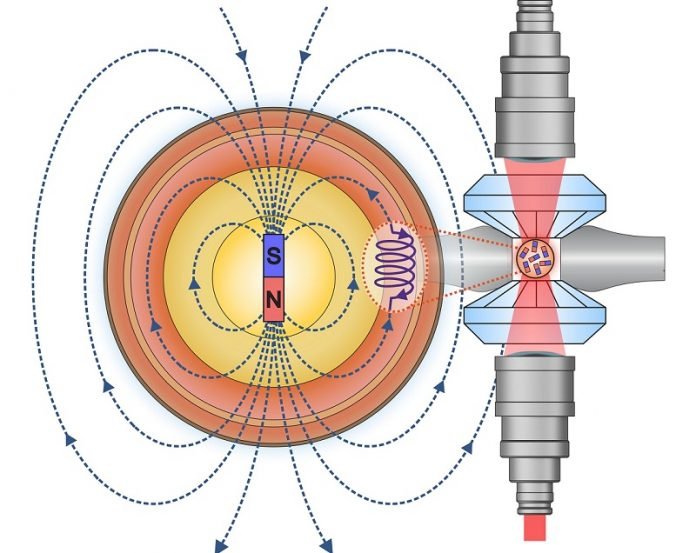

Now the scientists combined two methods. Using a so-called diamond anvil cell, they squeezed micrometric-sized samples of iron oxide hematite between two diamonds, and heated them with lasers to reach pressures of up to 90 gigapascal and temperatures of over 1,000 °C (1,300 K).

The researchers combined this method with so-called Mössbauer spectroscopy to probe the magnetic state of the samples by means of synchrotron radiation.

This part of the study was carried out at the ESRF synchrotron facility in Grenoble, France, and this made it possible to observe the changes of the magnetic order in iron oxide.

The surprising result was that the hematite remained magnetic up to a temperature of around 925 °C (1,200 K) – the temperature prevailing in the subducted slabs beneath the western part of Pacific Ocean at the Earth’s transition zone depth.

“As a result, we are able to demonstrate that the Earth’s mantle is not nearly as magnetically ‘dead’ as has so far been assumed,” says Prof. Carmen Sanchez-Valle from the Institute of Mineralogy at Münster University.

“These findings might justify other conclusions relating to the Earth’s entire magnetic field,” she adds.

Relevance for investigations of the Earth’s magnetic field and the movement of the poles

By using satellites and studying rocks, researchers observe the Earth’s magnetic field, as well as the local and regional changes in magnetic strength.

Background: The geomagnetic poles of the Earth—not to be confused with the geographic poles—are constantly moving.

As a result of this movement they have actually changed positions with each other every 200,000 to 300,000 years in the recent history of the Earth.

The last poles flip happened 780,000 years ago, and last decades scientists report acceleration in the movement of the Earth magnetic poles.

Flip of magnetic poles would have profound effect on modern human civilization. Factors which control movements and flip of the magnetic poles, as well as directions they follow during overturn are not understood yet.

One of the poles’ routes observed during the flips runs over the western Pacific, corresponding very noticeably to the proposed electromagnetic sources in the Earth’s mantle.

The researchers are therefore considering the possibility that the magnetic fields observed in the Pacific with the aid of rock records do not represent the migration route of the poles measured on the Earth’s surface, but originate from the hitherto unknown electromagnetic source of hematite-containing rocks in the Earth’s mantle beneath the West Pacific.

“What we now know—that there are magnetically ordered materials down there in the Earth’s mantle—should be taken into account in any future analysis of the Earth’s magnetic field and of the movement of the poles,” says co-author Prof. Leonid Dubrovinsky at the Bavarian Research Institute of Experimental Geochemistry and Geophysics at Bayreuth University.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-019-1254-8.