Scientists have been working for years to create robots powered by living muscle tissue.

These biohybrid robots combine lab-grown muscles with synthetic skeletons, giving them movements that resemble those of living creatures.

They can crawl, swim, grip objects, and even grow stronger over time.

But until now, their power and range of motion have been limited because living muscle alone is not very efficient at attaching to or moving rigid robotic parts.

A research team at MIT has introduced a groundbreaking solution: artificial tendons.

Their work, published in Advanced Science, shows that adding flexible, rubber band-like tendons made from hydrogel can dramatically boost the strength, speed, and durability of muscle-powered robots.

The idea comes from nature. In the human body, muscles do not directly attach to bones. Instead, tendons—strong but flexible tissues—connect muscles to the skeleton, allowing smooth and powerful movement.

Tendons also help protect muscles from tearing when they pull against hard bone. Professor Ritu Raman, an assistant professor of mechanical engineering at MIT and the study’s lead author, wondered whether robotic muscles could benefit from a similar design.

To test this idea, the researchers created a “muscle–tendon unit.” They grew a small strip of living muscle using standard lab techniques.

Then they attached artificial tendons made from a tough, stretchy hydrogel to either end of the muscle.

Hydrogel might sound flimsy, but modern hydrogel materials—especially those designed by MIT professor Xuanhe Zhao, a co-author of the study—can be surprisingly strong and sticky, able to bond to both biological tissue and synthetic materials.

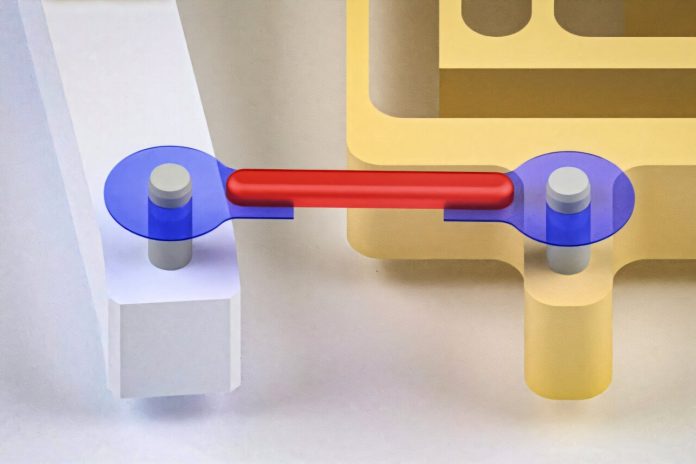

Once the team had their muscle-tendon unit, they connected the ends of the hydrogel tendons to the fingers of a robotic gripper. When they electrically stimulated the living muscle, it contracted, pulling on the tendons and causing the robotic fingers to pinch together.

The results were dramatic.

The gripper moved its fingers three times faster and generated 30 times more force than a similar robot powered by muscle alone. Even more impressive, the system kept working smoothly for over 7,000 contraction cycles. The new setup also boosted the robot’s power-to-weight ratio by eleven times, meaning the robot could do much more work with far less muscle tissue.

This breakthrough solves a long-standing problem in biohybrid robotics. Without tendons, engineers have had to use large amounts of muscle just to attach tissue securely to a rigid frame. Much of the muscle’s power was wasted, and the soft tissue often tore or detached.

With artificial tendons, only a small central piece of muscle is needed—the tendons handle the hard work of connecting to the robot’s skeleton and transmitting forces efficiently.

Raman explains that this mimics the body’s own solution to the challenge of connecting soft muscle to hard bone.

Tendons act like cables that can flex, stretch, and wrap around joints. By introducing an engineered version of these connectors, the team has created a modular system that can be attached to many different robotic designs. In the future, muscle-tendon units could serve as interchangeable building blocks for a wide range of biohybrid robots.

Experts in the field are enthusiastic about this advancement. Simone Schürle-Finke, a biomedical engineer at ETH Zürich who was not involved in the research, notes that the artificial tendons create a more realistic muscle–tendon–bone structure that greatly improves performance and durability.

She believes this moves the field closer to developing muscle-powered machines that can function outside the lab.

Biohybrid robots have exciting potential. Because muscle cells can grow stronger with exercise and heal after injury, future robots could adapt to their surroundings, repair themselves, and explore environments too dangerous or remote for humans. They could also perform delicate surgical tasks inside the body with unparalleled precision.

Raman’s team is already working on the next steps.

They plan to design protective skin-like coverings and other supportive structures to help muscle-powered robots survive and operate in real-world settings. With the help of artificial tendons, the future of robotics may be powered not only by electronics but also by living muscle—smartly connected to machines.