Scientists have discovered that humans may possess a surprising ability — a kind of “remote touch” that allows us to sense objects buried beneath materials like sand before we actually touch them.

The finding, made by researchers at Queen Mary University of London and University College London, reveals that our sense of touch is far more powerful and complex than we ever realized.

Traditionally, touch has been considered a “close-range” sense, limited to what we can physically contact.

But in nature, some animals can detect objects at a distance through mechanical signals that travel through the environment.

Shorebirds like sandpipers and plovers, for example, use their sensitive beaks to feel prey hidden under sand by detecting tiny vibrations and pressure changes.

The new study, presented at the IEEE International Conference on Development and Learning (ICDL), set out to test whether humans might have a similar ability.

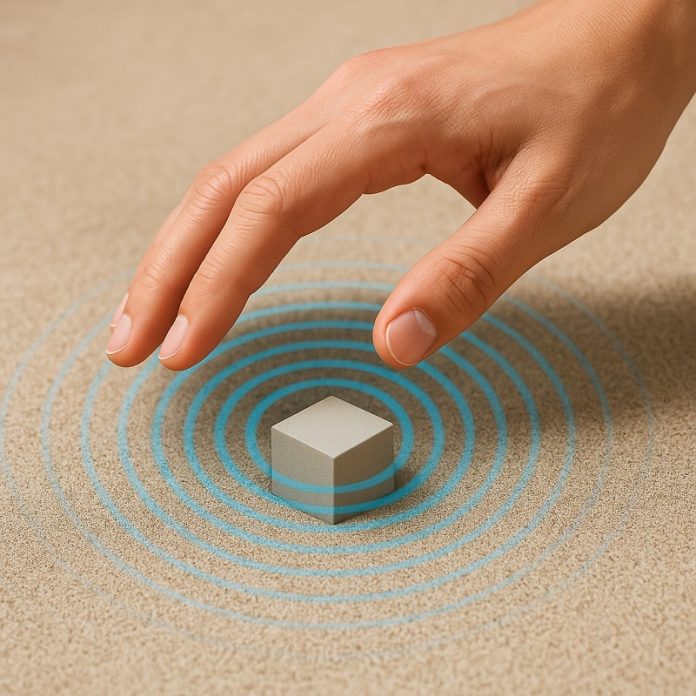

In a series of experiments, volunteers were asked to gently move their fingers through sand and identify where a small cube was buried — without touching it directly.

The results were surprising. Participants could often detect the hidden object before making contact, suggesting that human hands can sense minute disturbances in the surrounding material.

These subtle cues — mechanical “reflections” of movement in the sand bouncing off the buried cube — provided enough information for participants to estimate the object’s location.

By modeling the physics behind this phenomenon, researchers found that human tactile sensitivity comes remarkably close to the theoretical limit of what is physically detectable.

In other words, our hands are almost as sensitive as possible under the laws of physics when it comes to perceiving vibrations through sand-like materials.

To compare human performance with machines, the team also tested a robotic tactile sensor trained with an advanced artificial intelligence algorithm known as a Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) network.

The robot was able to sense objects from slightly greater distances but made more mistakes overall. While humans achieved about 70.7% accuracy, the robot reached only 40% accuracy because it often detected objects that weren’t actually there.

The results show that humans can genuinely detect objects without direct contact — something that had never been demonstrated before.

“It’s the first time that remote touch has been studied in humans, and it changes our conception of the perceptual world,” said Dr. Elisabetta Versace, Senior Lecturer in Psychology at Queen Mary University of London, who led the human experiments.

The research has important implications beyond human biology. By understanding how people sense objects through touch alone, scientists can design better robotic systems and assistive devices.

Robots modeled on human tactile sensitivity could safely locate fragile artifacts underground, explore hazardous environments, or search through sand and dust on Mars — all without relying solely on vision.

“This discovery opens possibilities for designing tools and technologies that extend human tactile perception,” said Ph.D. student Zhengqi Chen, who worked on the project. “It could inspire new types of robots capable of performing delicate tasks in challenging environments.”

Dr. Lorenzo Jamone, Associate Professor in Robotics and AI at University College London, added that the collaboration between psychology, robotics, and artificial intelligence made this study unique.

“The human experiments helped teach the robot how to ‘feel,’ and in turn, the robot’s results gave us new ways to interpret the human data,” he said. “It’s a perfect example of how studying humans and machines together can lead to both scientific insight and technological innovation.”

This discovery not only redefines what our sense of touch can do but also reveals that humans, like sandpipers, may possess a hidden “seventh sense” — the remarkable ability to feel the unseen.