Astronomers have made an exciting breakthrough in the search for the universe’s most mysterious substance—dark matter.

They have discovered the lowest-mass dark object ever detected using a powerful technique called gravitational lensing.

Dark matter is one of the biggest puzzles in science. Unlike stars or planets, it doesn’t shine or emit any light.

Yet it makes up most of the matter in the universe and shapes how galaxies form and move.

Scientists want to know if dark matter is spread smoothly across space or if it forms small, clumpy structures. The answer could reveal what dark matter is really made of.

Since dark matter cannot be seen directly, astronomers look for its effects on light. When light from a very distant galaxy passes near a massive object, that object’s gravity bends the light like a lens.

This warping of light, known as gravitational lensing, can reveal hidden objects—even ones that give off no light at all.

Devon Powell from the Max Planck Institute for Astrophysics, lead author of the new study published in Nature Astronomy, explained the challenge: “Hunting for dark objects that do not seem to emit any light is clearly difficult.

Since we can’t see them directly, we instead use very distant galaxies as a backlight to look for their gravitational imprints.”

To capture these faint signals, the team used a global network of radio telescopes, including the Green Bank Telescope in the U.S., the Very Long Baseline Array, and Europe’s Very Long Baseline Interferometric Network.

Together, they formed an Earth-sized super-telescope that could spot tiny distortions in light.

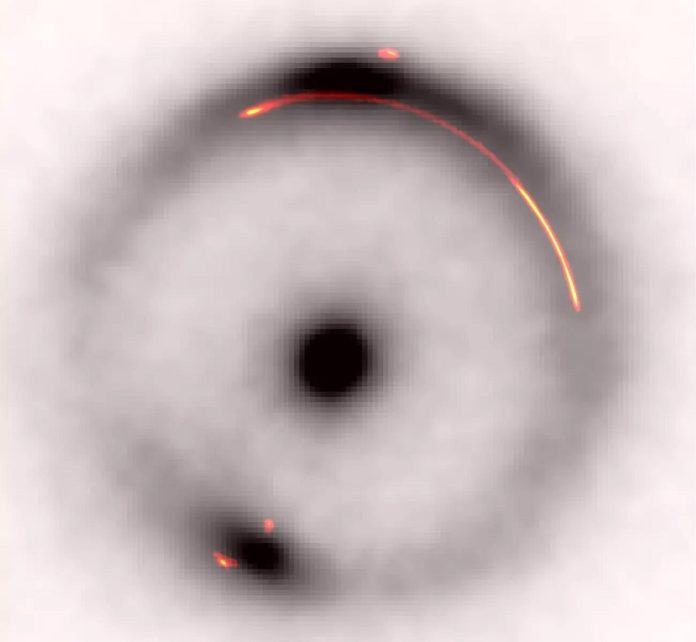

Their observations revealed a mysterious object with a mass about one million times that of our Sun. This clump of dark matter sits roughly 10 billion light-years away, back when the universe was only about 6.5 billion years old.

“This is the lowest-mass object ever found using this technique, by a factor of 100,” said John McKean, who led the data collection. The team immediately noticed a “pinch” in the light arc of a distant galaxy—an unmistakable sign of another mass hiding in the way.

The object itself does not shine in visible, infrared, or radio light. On telescope images, it appears only as a subtle white mark at the pinch point of the distorted galaxy arc. To understand it, the team had to build new computer models and run them on powerful supercomputers, since the dataset was massive and had never been analyzed in this way before.

Simona Vegetti, also from the Max Planck Institute, explained that every galaxy is expected to contain many dark matter clumps. “Finding them and convincing the community they exist requires a huge amount of number-crunching,” she said.

The discovery matches predictions from the “cold dark matter” theory, the leading idea about how galaxies form. Now, the scientists want to search for more of these low-mass dark clumps. If such objects are found in greater numbers, they will either confirm or challenge existing theories about dark matter.

As Powell put it, “Having found one, the question now is whether we can find more and whether their number still agrees with the models.” If not, it could reshape our understanding of the invisible substance that makes up most of the universe.

Source: Max Planck Society.