For years, scientists have known that the gut and brain communicate, but much of that conversation was thought to happen slowly, through hormones or immune responses.

Now, researchers at Duke University School of Medicine have discovered something entirely new: a rapid signaling system that allows the brain to respond in real time to messages from microbes in the gut.

They are calling it a “neurobiotic sense,” a newly identified “sixth sense” that could reshape how we understand eating, mood, and health.

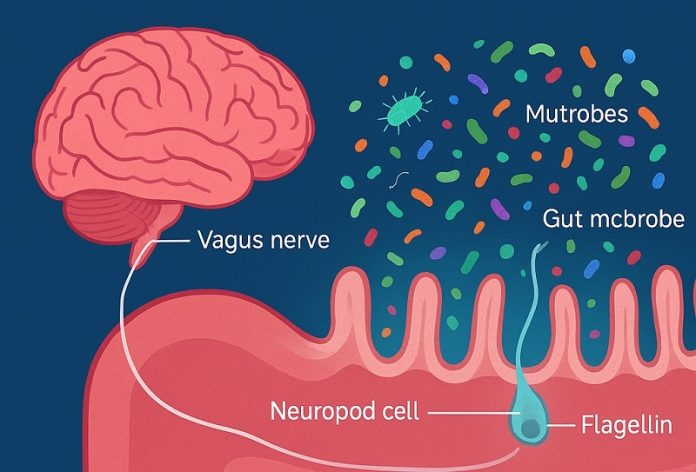

At the center of this discovery are neuropods, tiny sensor cells that line the wall of the colon.

These cells act like messengers, capable of detecting proteins released by gut microbes and quickly sending signals to the brain.

The team found that neuropods respond to a bacterial protein called flagellin, a key component of the tail-like structures that bacteria use to swim.

When food is eaten, certain gut bacteria release flagellin. Neuropods detect it with the help of a receptor called TLR5 and immediately send a signal through the vagus nerve, one of the body’s main communication pathways between the gut and brain.

The message is simple: stop eating. In this way, the microbes in the gut can directly influence behavior by curbing appetite.

To test the theory, the scientists carried out an experiment with mice. After fasting them overnight, they gave some mice a small dose of flagellin directly into the colon.

Those mice ate less food afterward. But when the same experiment was tried in mice genetically engineered to lack the TLR5 receptor, the animals kept eating and gained more weight. The difference suggested that without this receptor, the gut could not deliver the “we’ve had enough” signal to the brain.

The study, published in Nature, was led by neuroscientists Diego Bohórquez and M. Maya Kaelberer, along with graduate students Winston Liu and Emily Alway, and postdoctoral fellow Naama Reicher.

Together, they showed that this pathway represents a brand-new way microbes can shape our behavior, not through slow inflammation or chemical changes, but through immediate neural signals.

“This work shows that our behavior can be influenced directly by microbes in our gut,” said Bohórquez. He believes the discovery opens the door to future research into how diet might alter the microbiome and, in turn, how that affects conditions like obesity or even mental health disorders.

While the research is still in its early stages, the implications are far-reaching. If scientists can learn how different diets shape microbial activity, and how neuropods and the brain respond, it could lead to new strategies for treating overeating, obesity, and possibly even psychiatric illnesses.

For now, the discovery of this neurobiotic sense offers a fascinating glimpse into the hidden world inside us—a world where tiny microbes may be guiding our behavior in ways we are only just beginning to understand.

If you care about health, please read studies about why beetroot juice could help lower blood pressure in older adults, and potassium may be key to lowering blood pressure.

For more health information, please see recent studies about rosemary compound that could fight Alzheimer’s disease, and too much of this vitamin B may harm heart health.