Black holes are already some of the strangest objects in the universe, but a new discovery suggests that when two of them collide, there may be more to the story.

A team of astronomers from the Shanghai Astronomical Observatory (SHAO), part of the Chinese Academy of Sciences, has found the first strong evidence that a recent black hole merger wasn’t just a two-body event. Instead, the pair may have been orbiting a much larger, hidden “giant” at the same time.

The team, led by Dr. Han Wenbiao, studied a well-known gravitational wave event called GW190814, which was detected in 2019 by the LIGO and Virgo observatories.

This event was already unusual because the two black holes involved had an extreme size difference—one was about ten times bigger than the other. That kind of mismatch is rare, and it raised questions about how the pair came together in the first place.

Dr. Han and his colleagues believe the answer lies in the presence of a third object, likely a supermassive black hole.

Their results, published on July 21 in The Astrophysical Journal Letters, suggest that GW190814 didn’t happen in isolation but in the strong gravitational field of another compact object.

A triple black hole dance

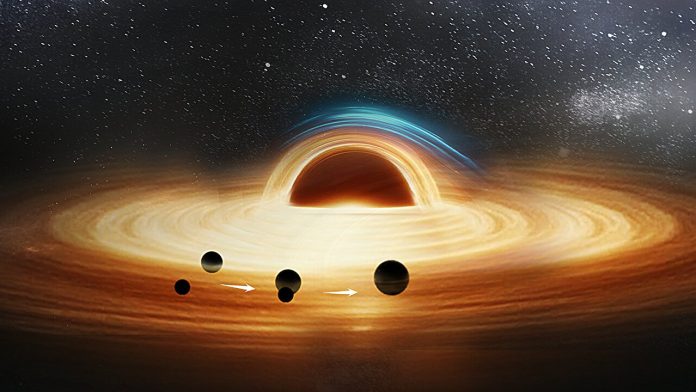

The team had previously proposed something called the “b-EMRI model”, which describes how a supermassive black hole could capture a pair of smaller black holes. Once trapped, the two would orbit the giant, forming a kind of cosmic triple system. While circling each other, the smaller black holes would also be circling the supermassive black hole, producing gravitational waves with telltale fingerprints across different frequencies.

To test this idea, the researchers examined the GW190814 signal in detail. They looked for signs of line-of-sight acceleration—a subtle shift in the signal that would occur if the merging black holes were also orbiting a third body. This effect slightly alters the gravitational wave frequency, much like the Doppler effect changes the pitch of a passing siren.

Evidence of a hidden giant

Using advanced computer models and Bayesian statistics, the team compared two scenarios: one where GW190814 was just an isolated binary black hole merger, and one where it happened under the gravitational pull of a third object. The second model fit the data much better.

They measured the line-of-sight acceleration at about 0.002 times the speed of light per second, and the statistical strength of the result was very high—about 58 to 1 in favor of the triple-system explanation. That makes this the first solid international evidence that a binary black hole merger took place near a third compact object.

A window into black hole origins

“This shows that black hole pairs may not always be lonely wanderers in space,” Dr. Han explained. “Instead, they could be part of more complex cosmic systems, shaped by the gravity of giants.”

With more powerful detectors like the Einstein Telescope, Cosmic Explorer, and space missions such as LISA, Taiji, and TianQin, astronomers will be able to track these signals with far greater accuracy. That means more discoveries like GW190814 may be just around the corner, helping scientists answer one of the universe’s biggest questions: how do black holes form, find each other, and eventually collide?

For now, the mystery deepens—binary black holes may have hidden giants pulling their strings.

Source: KSR.