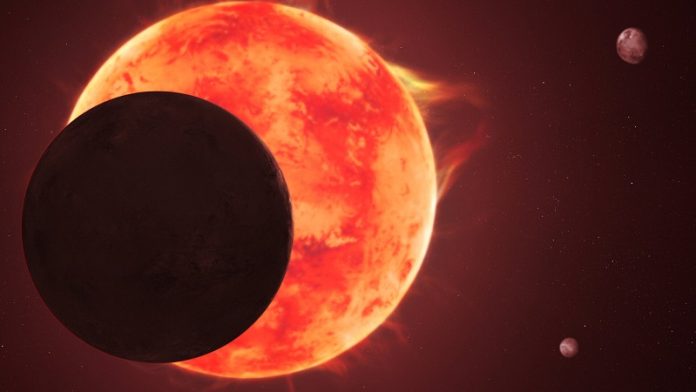

TRAPPIST-1 d has long fascinated astronomers as a possible Earth-like world beyond our solar system.

It is rocky, close to Earth in size, and sits on the edge of its star’s “habitable zone,” where temperatures might allow liquid water to exist. But new research using the NASA/ESA/CSA James Webb Space Telescope shows that TRAPPIST-1 d does not have an atmosphere like Earth’s, making it far less likely to be habitable.

Earth’s friendly environment—complete with a protective atmosphere, a stable sun, and abundant liquid water—makes it unique.

Scientists want to know whether such conditions could exist on other planets, even those orbiting very different stars. The TRAPPIST-1 system offers an ideal testing ground for this question.

Located about 40 light-years away, it contains seven Earth-sized rocky planets orbiting a cool, dim red dwarf star, the most common type of star in our galaxy.

“Ultimately, we want to know if something like Earth’s environment can exist elsewhere, and under what conditions,” said Caroline Piaulet-Ghorayeb of the University of Chicago and the Trottier Institute for Research on Exoplanets at Université de Montréal, lead author of the new study published in The Astrophysical Journal.

“At this point, we can rule out TRAPPIST-1 d as an Earth twin or cousin.”

TRAPPIST-1 d is the third planet from its star and completes one orbit—its “year”—in just four Earth days. Despite being in the star’s temperate zone, it orbits at only 2% of the distance between Earth and the Sun.

Webb’s Near-Infrared Spectrograph (NIRSpec) instrument looked for atmospheric molecules like water vapor, methane, and carbon dioxide, but found no clear evidence of them.

There are still several possible explanations. The planet could have an extremely thin atmosphere, like Mars, which would be difficult to detect. It might also have a dense, cloud-filled atmosphere like Venus, which could hide its chemical makeup. Or it may be a bare, airless rock.

Life is tough for planets around red dwarf stars. TRAPPIST-1 often sends out intense flares of high-energy radiation that can strip away atmospheres—especially for planets closer to the star. This makes finding atmospheres in such systems challenging, but also important, since red dwarfs are so common. If a planet can keep an atmosphere here, it could keep one almost anywhere.

“Webb’s sensitive infrared instruments are letting us probe the atmospheres of these small, cold planets for the first time,” said co-author Björn Benneke of Université de Montréal. “We’re just getting started in figuring out which planets can hold onto their atmospheres and which cannot.”

Attention now turns to the outer TRAPPIST-1 planets—e, f, g, and h. These worlds are farther from the star’s damaging radiation and may have a better chance of keeping their atmospheres. However, their colder temperatures and greater distances make detecting atmospheric gases more difficult, even for Webb.

“All hope is not lost for atmospheres around TRAPPIST-1 planets,” said Piaulet-Ghorayeb. “While we didn’t see a strong atmospheric signature on planet d, the outer planets could still have plenty of water and other gases.”

Ryan MacDonald, a co-author now at the University of St Andrews, added, “TRAPPIST-1 d may be a barren rock under the glare of a hostile red star, but the outer planets could still hold surprises.

Thanks to Webb, we know TRAPPIST-1 d is far from hospitable, and that makes Earth seem even more special.”