Astronomers have caught a rare type of black hole in the act of devouring a star—an event that lit up the universe in X-rays.

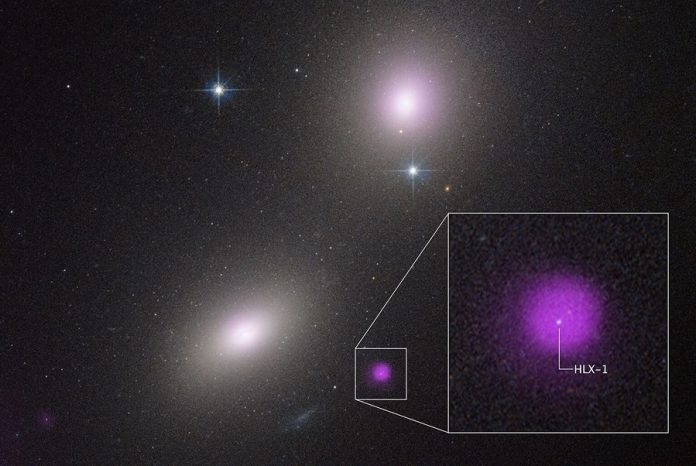

This rare black hole, known as NGC 6099 HLX-1, sits on the outskirts of a distant galaxy called NGC 6099, around 450 million light-years away in the constellation Hercules.

It’s believed to be an intermediate-mass black hole, or IMBH, a category that’s long been missing from astronomers’ black hole family tree.

NASA’s Hubble Space Telescope and Chandra X-ray Observatory worked together to detect and study this unusual object.

Intermediate-mass black holes are thought to weigh anywhere from a few hundred to a few hundred thousand times the mass of our sun—sitting between small black holes formed from dying stars and the gigantic supermassive black holes found at the centers of galaxies.

But IMBHs are hard to find because they don’t constantly swallow up material like their bigger cousins.

Instead, they quietly drift through space, only revealing themselves when something—like a nearby star—gets too close and is torn apart.

That’s exactly what happened here. In 2009, Chandra spotted a bright X-ray source outside the core of galaxy NGC 6099. Later observations showed that the black hole grew about 100 times brighter by 2012 and has been fading slowly ever since.

These changes are signs of a “tidal disruption event,” where a star wanders too close to a black hole and is pulled apart by its gravity. The hot gas from the shredded star forms a glowing disk around the black hole and produces powerful radiation, especially in X-rays.

Yi-Chi Chang, the lead author of the study from National Tsing Hua University in Taiwan, explained that X-ray sources like this one are rare outside of galaxy centers, making them important clues for finding IMBHs.

Around this black hole, the Hubble telescope also discovered a compact cluster of stars. This tightly packed group may serve as a buffet for the black hole, giving it plenty of material to consume over time.

The black hole’s location—around 40,000 light-years from the galaxy’s center—is also interesting. It’s far from the massive central black hole that likely sits quietly at the heart of NGC 6099.

The idea that galaxies can host these “satellite” black holes far from their centers helps scientists better understand how galaxies—and their central black holes—form and grow.

There are two main theories about the origins of supermassive black holes. One suggests that IMBHs merge over time to become giants, especially as galaxies collide and merge.

Another theory proposes that supermassive black holes formed directly from huge clouds of gas in the early universe, skipping the IMBH stage entirely. Discoveries like HLX-1 can help test these theories.

Future sky surveys with telescopes like the Vera C. Rubin Observatory in Chile could help find more of these rare feeding events.

If astronomers can spot enough of them, they’ll be able to study how often IMBHs tear apart stars, how many exist, and how they may help build the universe’s biggest black holes.

For now, HLX-1 offers a rare and valuable glimpse into the life of a mid-sized black hole caught in a cosmic feast.