While life seems like one long, continuous flow of experiences, our memories don’t work that way.

Instead of remembering everything as one big blur, our brains break life into smaller, meaningful moments—like chapters in a book.

This structure helps us understand what happened and when. But how does the brain know where one memory should end and the next should begin?

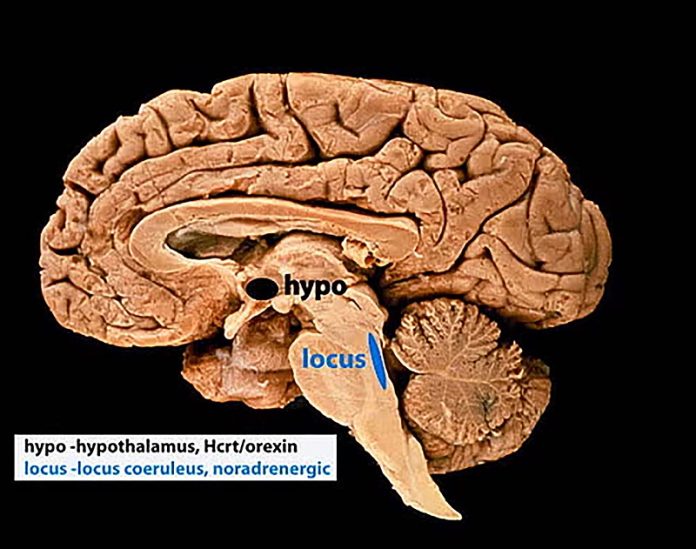

A new study from UCLA and Columbia University, published in Neuron, has found that a tiny region in the brain called the locus coeruleus may act like a reset button, helping us split continuous experiences into separate, memorable events.

Despite its small size, the locus coeruleus plays a powerful role in shaping how we remember our lives.

Psychology professor Dr. David Clewett and his team wanted to understand how the brain signals the start of a new memory.

Past research has shown that when we remain in the same context—like staying in the same room—our brains tend to group experiences together. But when something changes, like a sound or setting, it signals a boundary, and our brain marks that moment as the beginning of something new.

To test this, 32 volunteers were shown images while inside an MRI scanner. Meanwhile, simple tones were played in either their left or right ear. When tones repeated in the same ear, the brain registered them as one ongoing event.

But when the tones switched ears and pitch, people perceived them as a new event starting. This change in sound acted as an “event boundary.”

Later, participants were asked to recall the order of what they had seen. The study found that when the locus coeruleus was more active at these sound changes, people were more likely to store those moments as separate memories.

Brain scans showed that these boundary points also triggered changes in the hippocampus, the brain’s memory center. The researchers even confirmed locus coeruleus activity by measuring changes in pupil size, which tends to grow slightly when this brain region is active.

Interestingly, the study also found that people who live with chronic stress may have trouble forming clear memory boundaries.

That’s because the locus coeruleus has two modes: one that responds to important new events and one that handles general alertness and stress.

When the brain is always on high alert—like living with a nonstop fire alarm—it becomes harder to notice truly meaningful changes. People with high stress levels had weaker responses to event boundaries, which could make their memories feel more blurred and disorganized.

Understanding the role of the locus coeruleus may help researchers develop new treatments for memory-related conditions like PTSD and Alzheimer’s disease.

It also suggests that calming an overactive brain—through medication, deep breathing, or even stress balls—could help improve how we form and recall memories. Even though it’s one of the smallest parts of the brain, the locus coeruleus may have one of the biggest impacts on how we remember our lives.