Most of the water on Earth is salty ocean water—not suitable for drinking.

While desalination plants can remove the salt and make seawater drinkable, they use a lot of energy and expensive equipment.

But now, scientists have developed a lightweight, sponge-like material that uses only sunlight to turn seawater into clean, drinkable water.

This new method could lead to a much simpler and more sustainable way to get fresh water.

The breakthrough comes from a team of researchers led by Xi Shen, and their study was recently published in ACS Energy Letters.

They created a special type of aerogel—a rigid, sponge-like material full of tiny air pockets—that can absorb seawater and use sunlight to produce fresh water through evaporation.

This is not the first time that sunlight-powered materials have been used for water purification. In the past, scientists tested hydrogels, which are soft, water-filled materials, for cleaning water contaminated with heavy metals.

When placed under the sun, the hydrogels quickly evaporated clean water vapor, leaving pollutants behind. However, hydrogels aren’t ideal for long-term desalination.

Aerogels, on the other hand, are firmer and better at transporting water vapor. But until now, their performance dropped as the size of the material increased.

To solve this problem, Shen and his team created an aerogel using a paste made from carbon nanotubes and cellulose nanofibers. They 3D-printed this paste layer by layer onto a frozen surface, allowing each layer to freeze before the next was added. The result was a sturdy, spongy material filled with vertical pores, each about 20 micrometers wide.

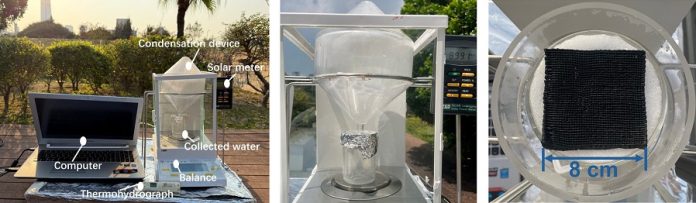

The researchers tested square pieces of the aerogel ranging from just 1 centimeter to 8 centimeters wide. They found that the material’s ability to evaporate water remained just as strong, even as the size increased—something previous aerogels couldn’t achieve.

To demonstrate its potential in real-world conditions, the team ran a test outdoors. They placed the aerogel into a cup of seawater and covered it with a clear plastic dome. Sunlight heated the surface of the aerogel, causing clean water vapor to rise.

The salt stayed behind. The vapor condensed on the plastic cover, then slid down into a funnel and collected in a beaker below. After just six hours in the sun, the setup produced about three tablespoons of drinkable water.

While it may not seem like much, this small test shows big promise. Shen says the new aerogel “allows full-capacity desalination at any size,” meaning it could be scaled up easily.

This could lead to a simple, low-cost way of creating clean water using nothing but the sun—especially useful in areas with limited resources or during emergencies.