MIT engineers have developed a new kind of low-cost, easy-to-use sensor that could bring fast and affordable disease testing to people around the world—even in places without access to clinics or labs.

These new sensors, made using DNA and a bit of clever chemistry, could one day help detect serious diseases like cancer, HIV, or the flu with just a small sample of urine, saliva, or a nasal swab.

The key innovation behind these sensors comes from using a CRISPR-based enzyme, part of the same gene-editing system known for cutting DNA.

But here, the enzyme is used in a different way: when it detects a specific disease marker, it turns into a kind of microscopic lawnmower, chopping up DNA attached to a small gold sensor.

This chopping causes a change in the electric signal that the sensor produces, which tells the user whether a disease marker is present.

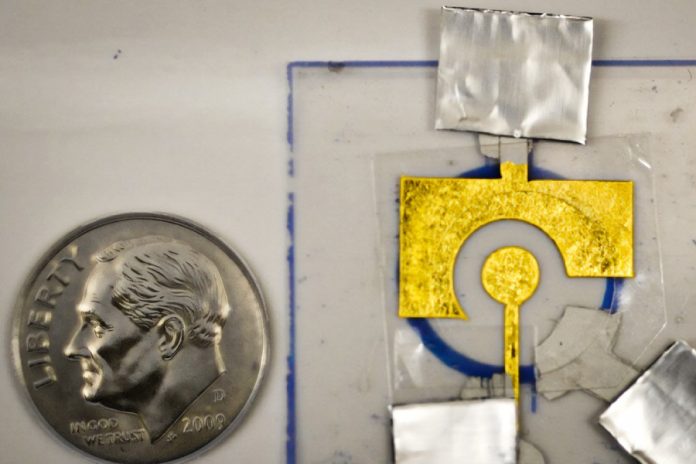

The entire sensor costs just 50 cents to make. According to MIT chemical engineering professor Ariel Furst, who led the research, these affordable sensors could make it possible for people to test themselves for diseases at home, without needing a lab or even a doctor’s office.

The team’s goal is to make medical testing easier and more accessible, especially in places with limited healthcare resources.

A big challenge with these DNA-based sensors is that DNA doesn’t last very long, especially when exposed to heat or air. Until now, the sensors had to be assembled just before use, which made it difficult to send them to faraway places or store them for long periods.

But the MIT team has solved that problem by adding a simple coating made of polyvinyl alcohol, a very cheap and widely available polymer. This coating acts like a protective tarp that shields the DNA from heat, air, and harmful chemicals.

Once the coating is dried on the sensor, it keeps the DNA stable for up to two months, even in temperatures as high as 150 degrees Fahrenheit.

When it’s time to use the sensor, the protective layer can be rinsed off with water, leaving the DNA ready to detect its target. The researchers tested the coated sensors and found that they still worked perfectly after storage, successfully identifying a gene linked to prostate cancer, known as PCA3.

This technology could be adapted to detect a wide variety of illnesses, simply by changing the CRISPR “guide” RNA to match the disease’s genetic fingerprint.

It works much like glucose meters used by people with diabetes, but instead of measuring sugar levels, it detects whether a disease is present based on how the enzyme changes the electric current.

The MIT team hopes to launch a startup to bring these sensors to real-world use, and they’ve joined the delta v accelerator program at MIT to help turn their idea into a product. Now that they can ship and store the sensors without needing refrigeration, they plan to test them in different environments and with actual patient samples.

Their ultimate aim is to make disease testing fast, cheap, and accessible to everyone—no matter where they live.

By turning advanced biotechnology into a simple, disposable test, these sensors could change the way the world diagnoses illness.

Source: MIT.