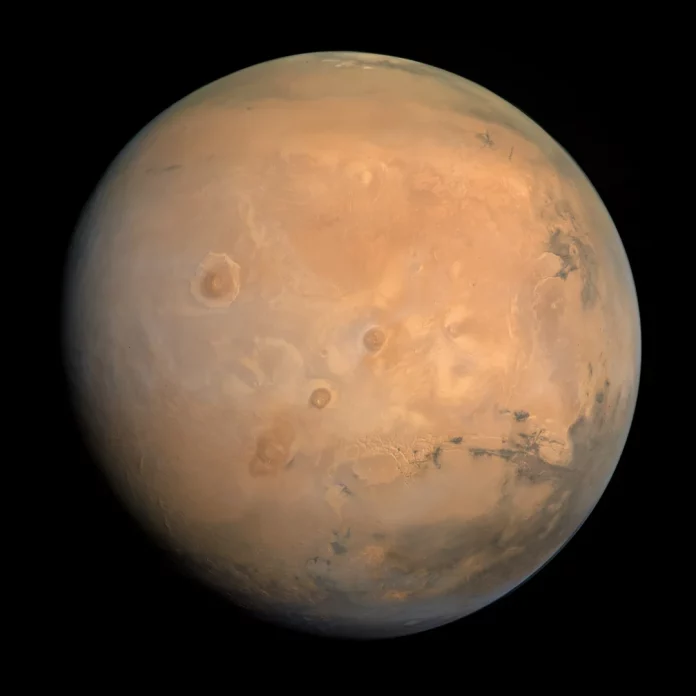

Mars, often called the Red Planet due to its distinctive rusty color from iron oxide on its surface, is Earth’s neighboring planet and humanity’s most likely next destination for exploration.

It’s about half the size of Earth and takes nearly two years to complete one orbit around the Sun.

Mars is home to the largest volcano in our solar system, Olympus Mons, as well as a massive canyon system called Valles Marineris.

It continues to fascinate scientists who are searching for signs of past or present life while planning for the day humans pay a visit.

Scientists have made a groundbreaking discovery that may well bring that first human exploration a little closer.

Researchers led by University of Mississippi planetary geologist Erica Luzzi have found strong evidence of water ice just beneath the Martian surface, a finding that could solve one of the biggest challenges facing future Mars missions.

The research team discovered indications of water ice less than one meter below the surface in Mars’ Amazonis Planitia region, located in the planet’s middle latitudes.

Using high-resolution satellite images from HiRISE on board the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter, the most powerful camera ever sent to another planet, they identified telltale signs including ice-exposing craters and polygonal terrain patterns that typically indicate near-surface ice.

Amazonis Planitia region represents the “perfect compromise” for future missions, according to Luzzi. The middle latitudes receive enough sunlight to power equipment while remaining cold enough to preserve ice deposits. This makes the region an ideal candidate for humanity’s first Mars landing site.

Water ice isn’t just about having something to drink, though that’s certainly important, but for Mars explorers, water represents a lifeline that could mean the difference between mission success and failure.

It can be broken down to provide oxygen for breathing and hydrogen for rocket fuel too, eliminating the need to transport the heavy resource from Earth.

“If we’re going to send humans to Mars, you need H2O and not just for drinking, but for propellant and all manner of applications,” Erica Luzzi, University of Mississippi.

This concept, called in situ resource utilization, is crucial for Mars missions because of the vast distances involved. While a resupply mission to the Moon takes about a week, reaching Mars requires months of travel time. Astronauts would need to be completely self-sufficient for extended periods.

Beyond supporting human missions, the ice discovery has exciting implications for astrobiology, the search for life beyond Earth. On our planet, ice can preserve biological markers from ancient life forms and even harbor living microorganisms in extreme environments.

While the satellite evidence is compelling, scientists emphasize that physical confirmation is still needed.

The next phase involves radar analysis to better understand the ice deposits’ depth and distribution. Eventually, robotic missions or human explorers will need to drill samples to confirm whether the formations are pure water ice or contain other materials.

This research, published in the Journal of Geophysical Research: Planets, represents a crucial stepping stone toward establishing a human presence on Mars.

While astronauts may still be years away from setting foot on the Red Planet, scientists now have a much clearer idea of where those historic first steps should be taken.

Written by Mark Thompson/Universe Today.