Mars may seem like a dry and lifeless planet today, but billions of years ago, it was much wetter—and possibly more welcoming to life.

A new study published in Nature Astronomy suggests that thick layers of clay found on Mars could have been stable, life-friendly environments during the planet’s ancient past.

The research, led by Rhianna Moore while she was a postdoctoral fellow at The University of Texas at Austin, focuses on large clay deposits scattered across the Martian surface.

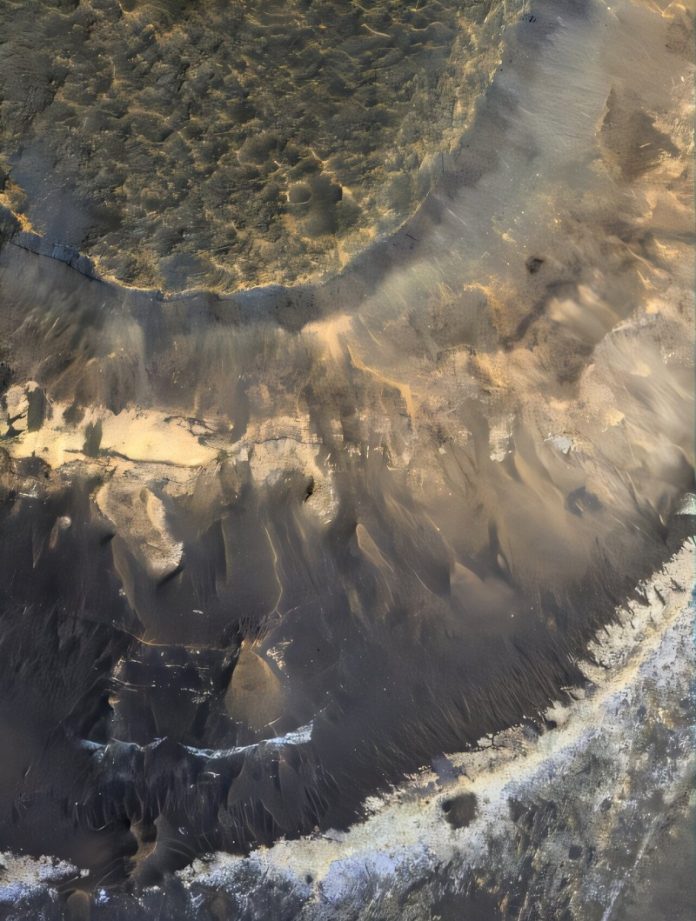

These clays can span hundreds of feet in thickness and are of great interest to scientists because their formation requires water.

That makes them potential hotspots for signs of ancient life.

Moore, who now works with NASA’s Artemis mission team, analyzed 150 clay-rich areas previously mapped by NASA’s Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter.

By studying their elevation and nearby landforms, she found that these clays mostly formed in low-lying areas near ancient lakes. These regions were wet but relatively calm, without strong water flows that would disturb or erode the landscape.

According to Moore, the calm, stable conditions in these spots could have allowed for the long-term presence of water and minerals—key ingredients for life.

On Earth, similar environments are known to support thick clay deposits in tropical, humid areas where chemical weathering is strong, but physical erosion is minimal.

Co-author Tim Goudge, a geoscientist at UT Austin, noted that these Martian sites reflect that same balance.

What makes this discovery even more intriguing is how it ties into the bigger mystery of Mars’ ancient climate.

Mars once had lakes, rivers, and even rain, but much of its geological record doesn’t match Earth’s in some surprising ways.

One example is the puzzling lack of carbonate rocks on Mars—rocks that should have formed if there was abundant CO₂ in the atmosphere interacting with volcanic rock and water, just as they do on Earth.

Moore and her team suggest that the ongoing formation of clay may have played a role in this discrepancy. As clays formed, they may have trapped water and chemical byproducts inside themselves, preventing those materials from reacting with the surrounding environment to form carbonates.

On Earth, the shifting of tectonic plates brings new rock to the surface, allowing it to react with water and help regulate the climate.

But Mars lacks such geological recycling. When its volcanoes released carbon dioxide, there wasn’t enough fresh rock around to absorb the gas, which may have caused the planet to warm and become wetter temporarily—contributing to the formation of these thick clays.

Overall, the study paints a picture of ancient Mars as a place where water, minerals, and environmental stability came together to possibly support life. These thick clay deposits could be the key to unlocking secrets about Mars’ climate history—and whether life ever had a chance to begin there.

Source: University of Texas at Austin.