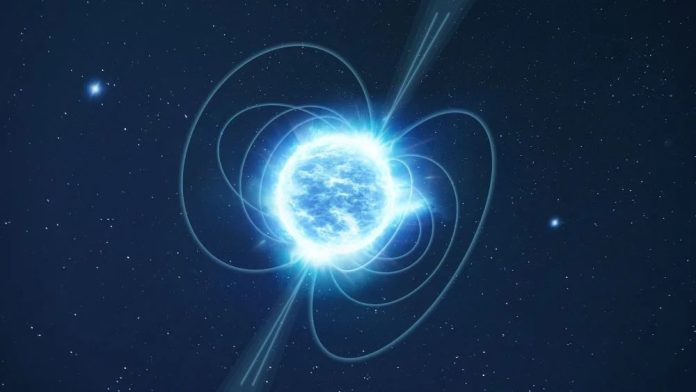

When massive stars explode as supernovae, they can leave behind neutron stars.

Other than black holes, these are the densest objects we know of. However, their masses are difficult to determine. New research is making headway.

In new research published in Nature Astronomy, a team of researchers analyzed a sample of 90 neutron stars in binary relationships to try to measure the birth mass function (BMF) of neutron stars.

It’s titled “Determination of the birth-mass function of neutron stars from observations.” The lead author is Zhi-Qiang You from the School of Physics and Astronomy, Beijing Normal University, Beijing, China.

The BMF of neutron stars is a key research area in astrophysics. The BMF describes how mass is distributed among neutron stars immediately after they form in supernova explosions.

Like all aspects of nature, its related to multiple other things, like understanding the final stages of massive stars and the gravitational waves from mergers between neutron stars and black holes.

The BMF can also give scientists insights into the properties of matter at extreme densities.

“Understanding the birth masses of neutron stars is key to unlocking their formation history,” said Dr. Simon Stevenson, an OzGrav researcher at Swinburne University and co-author of the study.

“This work provides a crucial foundation for interpreting gravitational wave detections of neutron star mergers.”

“The birth mass function of neutron stars encodes rich information about supernova explosions, double star evolution, and properties of matter under extreme conditions,” the authors explain in their paper.

“To date, it has remained poorly constrained by observations, however.”

Early observations of neutron star (NS) masses developed only loose constraints on their masses, partly hampered by limited observational data.

“For a long time, all observed neutron-stars masses were in a narrow range, consistent with a Gaussian distribution, with a mean of 1.35 solar masses and a width of 0.04 solar masses,” the authors write.

A Gaussian distribution forms a bell curve when graphed and the highest point is the mean. In textbooks and in studies, a mean mass of 1.4 solar masses is routinely used for NSs.

As time went on, this number became less reliable, especially as researchers found NSs with masses greater than two solar masses.

In this work the researchers examined 90 NSs in binary relationships and came up with a power law that describes the BMF.

“To determine the neutron-star mass distribution, we compiled a sample of 90 neutron stars for which well-determined mass estimates are available from observations of radio pulsars, gravitational waves and X-ray binaries,” the authors write. Part of the complexity is that mass can be transferred between objects when NSs are in binary relationships.

In their work, they classified the NSs as either recycled or non-recycled (slowly rotating) neutron stars. Recycled neutron stars are ones that have spun up to extremely high rotational speeds due to accreting matter from their companion.

“When constraining the birth-mass function of neutron stars, the key difference between the two subclasses is that observed masses of recycled pulsars need to be corrected for mass accreted throughout the recycling process, whereas the measured masses of slow neutron stars should equal their birth masses, as no mass-gaining process occurred,” the authors explain.

They then applied “probabilistic corrections to account for mass accreted by recycled pulsars in binary systems to mass measurements of 90 neutron stars.”

These probabilistic corrections allowed the researchers to infer the initial masses of neutron stars at the time of formation.

From this, they developed a new model for the BMF, a power-law distribution (PLD). PLDs are different than Gaussian distributions. In a PLD, one quantity varies as a power of another. PLDs are common in both human systems like wealth distribution and city populations and in natural systems like earthquake magnitudes, where it shows that smaller Earthquakes are much more frequent than larger ones.

The PLD shows that NS masses “can be described by a unimodal distribution that smoothly turns on at 1.1 solar masses, peaks at 1.27 solar masses, before declining as a steep power law.”

“Our approach allows us to finally understand the masses of neutron stars at birth, which has been a long-standing question in astrophysics,” said co-author Prof. Xingjiang Zhu from Beijing Normal University, China.

The new model illustrates a link between the neutron star BMF and the initial mass function (IMF) of massive stars.

“The power-law shape may be inherited from the initial mass function of massive stars, but the relative dearth of massive neutron stars implies that single stars with initial masses greater than ~18 solar masses do not form neutron stars, in agreement with the absence of massive red supergiant progenitors of supernovae,” the authors write.

The results extend to astrophysicists’ study of gravitational waves and other astrophysical phenomena.

“Understanding the birth masses of neutron stars is key to unlocking their formation history,” said Dr. Simon Stevenson, an OzGrav researcher at Swinburne University and co-author of the study. “This work provides a crucial foundation for interpreting gravitational wave detections of neutron star mergers.”

Written by Evan Gough/Universe Today.