A team of physicists, led by Jonathan Richardson from the University of California, Riverside, has made a breakthrough in gravitational-wave detection.

Their research, published in Physical Review Letters, introduces a new optical technology that could greatly enhance the capabilities of observatories like LIGO (Laser Interferometer Gravitational-Wave Observatory).

This innovation may also play a key role in future observatories, such as the planned Cosmic Explorer.

What are gravitational waves?

Gravitational waves are ripples in space-time, predicted by Einstein’s theory of general relativity.

They occur when massive objects, like black holes or neutron stars, collide or move rapidly.

These waves carry energy and information, helping scientists study extreme astrophysical objects and the nature of the universe itself.

How does LIGO work?

LIGO consists of two giant laser interferometers—one in Washington State and the other in Louisiana.

Each has two 4-kilometer-long arms that use laser beams to detect tiny distortions in space-time caused by passing gravitational waves.

Since it began operating in 2015, LIGO has detected around 200 gravitational-wave events, mostly from black hole mergers.

To improve LIGO’s sensitivity and detect even fainter gravitational waves, scientists need to increase the laser power inside the detectors to over 1 megawatt.

However, this creates problems. When high-powered lasers hit LIGO’s 40-kilogram mirrors, they cause heating and distortions that reduce accuracy.

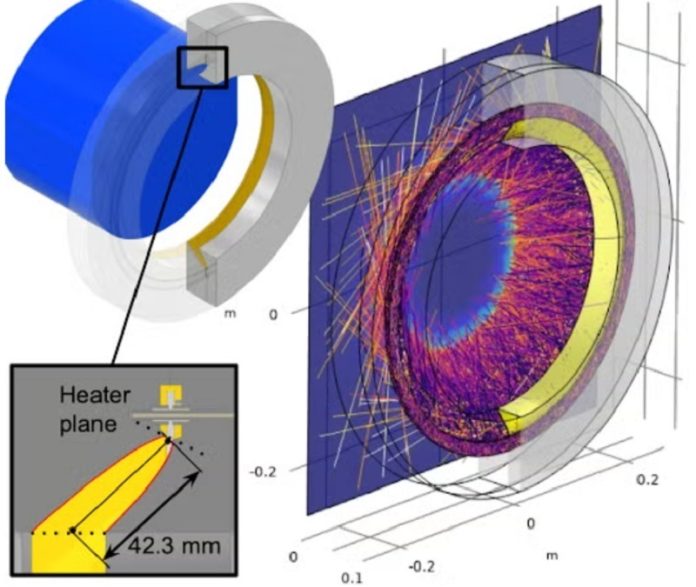

Richardson’s team has developed an advanced adaptive optics system that can correct these distortions.

The system uses precise infrared radiation to adjust the mirrors’ surfaces in real time. This is the first time such a technique has been applied to gravitational-wave detection.

By reducing noise and improving mirror performance, this technology will allow LIGO to reach much higher laser power levels than before.

Cosmic Explorer is a next-generation observatory planned for the future. It will be 10 times the size of LIGO, with 40-kilometer-long arms.

When completed, it will be the largest scientific instrument ever built, allowing scientists to observe the universe as it was before the first stars formed—about 14 billion years ago.

This new technology could help answer some of the biggest questions in physics. Scientists are still debating the exact rate at which the universe is expanding, and gravitational waves could help settle this mystery.

The improved detectors will also provide detailed insights into black holes, allowing researchers to test Einstein’s theories and explore new physics.

By enhancing LIGO and paving the way for Cosmic Explorer, Richardson’s team is pushing the boundaries of what we can learn from gravitational waves, bringing us closer to unlocking the secrets of the universe.