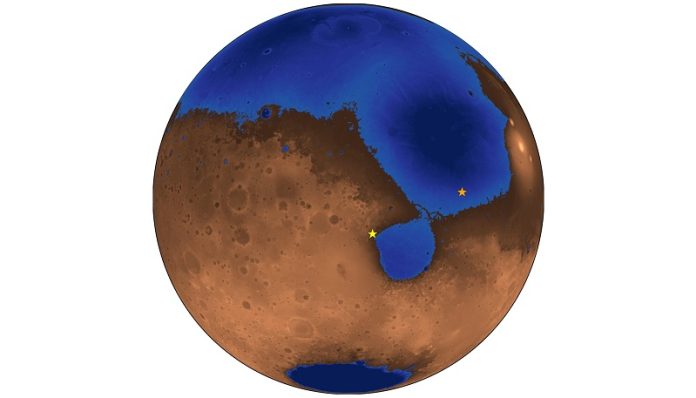

A Chinese rover that landed on Mars in 2021 has found strong evidence that the planet once had a vast ocean.

Scientists believe this discovery adds to the growing proof that Mars was once much wetter than it is today.

The rover, named Zhurong, was part of China’s Tianwen-1 mission. It explored Mars for about a year, from May 2021 to May 2022, before becoming inactive.

During its journey, Zhurong traveled 1.9 kilometers (1.2 miles) in a region thought to be an ancient shoreline, dating back 4 billion years—a time when Mars had a thicker atmosphere and a warmer climate.

How did scientists find evidence of an ancient ocean?

The key tool used in this discovery was ground-penetrating radar (GPR). This technology allows scientists to see what lies beneath the surface, just like how radar on Earth can detect underground pipes or hidden structures.

Zhurong’s radar probed as deep as 80 meters (260 feet) underground, revealing layers of material that sloped toward the shoreline at a 15-degree angle—a pattern very similar to beaches on Earth.

Scientists say these thick layers of sand-like deposits would have taken millions of years to form, suggesting that Mars had a long-lasting ocean with waves that shaped its shoreline. The radar also showed that these deposits were made of particles similar to beach sand, rather than wind-blown dunes, which are common on Mars.

Michael Manga, a scientist from the University of California, Berkeley, explained:

“These structures don’t look like sand dunes, impact craters, or lava flows. They match the patterns we see in ocean beaches on Earth. Their angle and orientation suggest they formed along an ancient Martian shoreline.”

If Mars once had beaches, that means it also had an ice-free ocean with flowing water. This suggests that rivers must have carried sediments into the ocean, just like they do on Earth. The presence of water, sediment, and possibly nutrients means Mars may have had conditions suitable for life.

Benjamin Cardenas, a researcher from Penn State University, highlighted the significance:

“Shorelines are great places to search for signs of past life. On Earth, early life likely started in places like this, near shallow water and air.”

Hai Liu, a scientist from Guangzhou University, also noted:

“This strengthens the case that Mars was once habitable, at least in some regions.”

A long debate about Mars’ oceans

Scientists have debated for decades whether Mars once had an ocean. In the 1970s, NASA’s Viking spacecraft took pictures of what looked like an ancient shoreline across Mars’ northern hemisphere. However, this shoreline had many irregular ups and downs, leading scientists to doubt it was really formed by water.

Some theories suggest that Mars’ giant volcanoes might have caused shifts in the planet’s surface over time, making an old shoreline appear uneven. In 2017, researchers proposed that Mars’ rotation changed as volcanic regions grew, which could explain the unusual shape of the suspected shoreline.

The discovery made by Zhurong helps strengthen the idea that Mars once had an open ocean with waves and tides that shaped sandy beaches.

What happened to the water?

If Mars once had a large ocean, where did all the water go? Scientists believe much of it escaped into space as Mars lost its atmosphere over time. Some water may also have gone underground, either frozen as ice or locked into minerals in rocks.

In other recent studies, NASA’s Curiosity and Perseverance rovers found signs of ancient lakes on Mars. They discovered evidence of ripples in sediments, which could have formed in long-gone bodies of water. However, these craters were small lakes, not vast oceans.

Michael Manga emphasized:

“To create ripples in a lake, you need liquid water. Now we’re seeing beaches, which suggest we had an entire ocean.”

A hidden, well-preserved beach

Over time, dust storms, volcanic eruptions, and asteroid impacts likely buried the ancient shoreline under thick layers of material. This actually helped preserve the beach deposits, keeping them undisturbed beneath the surface for billions of years.

Benjamin Cardenas concluded:

“This is an incredible dataset. It’s rare to find shoreline deposits that haven’t been eroded over time. These are some of the best-preserved signs of an ancient Martian ocean we’ve ever seen.”

This discovery brings scientists one step closer to understanding Mars’ past climate and its potential for life. Future missions may explore these ancient beaches further, searching for clues about the planet’s watery history and whether life once existed there.