Scientists have discovered that deep trenches on Uranus’ moon Ariel might be pathways for material from its interior to reach the surface.

These findings could give us clues about Ariel’s hidden ocean and what lies beneath its icy crust.

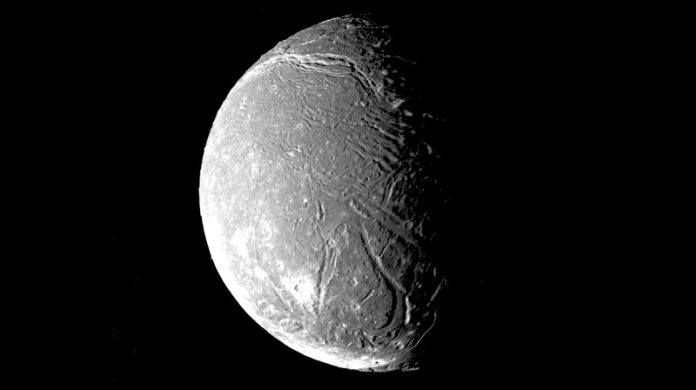

A new look at Ariel’s surface

Last year, planetary scientist Richard Cartwright from Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory (APL) suggested that carbon dioxide ice found on Ariel likely came from processes inside the moon—possibly from an underground ocean.

Now, a new study led by APL planetary geologist Chloe Beddingfield provides more insight into how these materials reach the surface.

Her team’s research, published on February 3 in the Planetary Science Journal, points to medial grooves—trenches cutting through Ariel’s large canyons—as the most likely paths for this exchange.

These grooves work similarly to spreading centers on Earth, where material from deep inside rises and forms new crust, like on the ocean floor.

“If we’re right, these grooves are the best places to find evidence of Ariel’s interior,” said Beddingfield. “No other features seem to bring material to the surface in the same way, making this discovery very exciting.”

Clues from Voyager 2

Scientists have long suspected that Ariel’s grooves formed due to volcanic or tectonic activity. To investigate, Beddingfield’s team analyzed images taken by NASA’s Voyager 2, the only spacecraft to visit Uranus. They found strong signs that these grooves act as spreading centers.

For example, if you digitally remove the canyon floors, the walls on each side fit together like puzzle pieces. Some canyon floors also have evenly spaced ridges, similar to tracks left by a construction machine, which suggests layers of material have built up over time.

These spreading centers likely formed because of heat from Ariel’s interior, which causes material to rise and push apart the crust. Tidal forces from Uranus and neighboring moons have also played a role, making Ariel go through cycles of warming, melting, and freezing.

Could Ariel still have an ocean?

Scientists believe these tidal forces may have once created an underground ocean inside Ariel and another Uranian moon, Miranda. A 2024 study even suggested that Miranda’s ocean could still exist today.

As for Ariel, researchers are still unsure. “The possible ocean inside Ariel may be too deep to interact with these grooves,” Beddingfield cautioned. “We also don’t know if the carbon dioxide we see is directly linked to them since Voyager 2 couldn’t map the ices in detail.”

To solve these mysteries, scientists say we need a spacecraft to visit Uranus and its moons. Cartwright emphasized that an orbiter could fly close to Ariel, study its grooves, and check for carbon-based materials. “If these molecules are concentrated along the grooves, it would strongly support the idea that they’re windows into Ariel’s interior,” he said.

With interest in Uranus growing, a future mission could give us an incredible look at Ariel’s past—and maybe even its present.

To learn more about APL’s research on Uranus and its moons, visit the Ice Giant Research and Exploration page.