The nature of dark matter has been a hotly debated topic for decades.

If it’s a heavy, slow moving particle then it’s just possible that neutrinos may be emitted during interactions with normal matter.

A new paper proposes that Jupiter may be the place to watch this happen.

It has enough gravity to capture dark matter particles which may be detectable using a water Cherenkov detector.

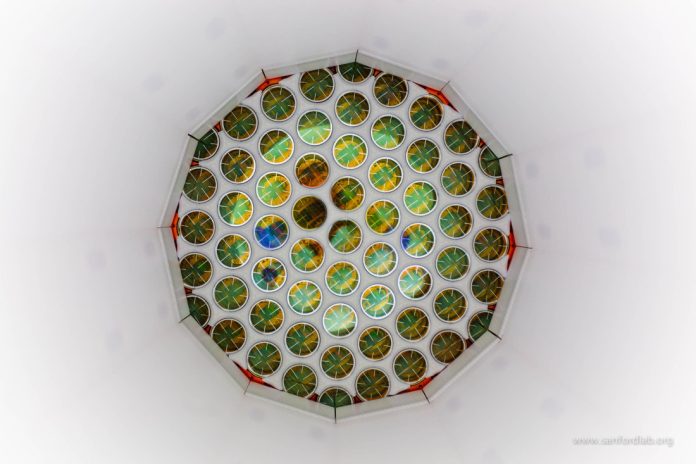

The researchers suggest using a water Cherenkov detector to watch for excess neutrinos coming from the direction of Jupiter with energies between 100 MeV and 5 GeV.

Jupiter is the largest planet in the solar system, large enough to swallow up all the planets and have a little room to spare.

It’s composed mainly of hydrogen and helium and is devoid of a solid surface. Of all the planets, Jupiter has a powerful magnetic field and a strong gravitational field.

It’s gravitational field is so powerful that, over the years, it has attracted, and even destroyed comets like Shoemaker-Levy 9 back in 1994.

Of all the features visible in the planet’s atmosphere, the giant storm known as the Great Red Spot is by far the most prominent.

Planets in the solar system would, until now, be the last place to go hunting for dark matter.

This mysterious stuff is invisible to all normal detection methods but is thought to make up 27% of the universe, outweighing visible matter at 5% (the majority of remainder made up of dark energy.) As its name suggests, dark matter doesn’t emit, absorb or reflect light making it hard to observe.

It’s existence has been inferred from the gravitational effects on galaxies, galaxy clusters and the largest scale structures of the universe. Despite its prominence in the universe, the nature of it remains largely unknown.

Dark matter is measured in GeV because this is a standard method in high energy physics to express the mass of particles. Until recently attempts to detect dark matter have relied upon experiments where dark matter is scattered with electrons, protons or neutrons in a detector. The interactions cause energy transfers which then reveal he presence of dark matter.

In a paper by Sandra Robles from Kings College London and Stephan Meighen-Berger from the University of Melbourne, they propose and calculate the level of annihilating dark matter neutrinos within Jupiter and whether they could be detected using existing neutrino observatories.

The team also propose a way to use of water Cherenkov detectors which are designed to detect high-energy particles such as neutrinos or cosmic rays. This is achieved by capturing Cherenkov radiation emitted while they travel through water.

To give context to the process, the radiation is optical and occurs when a charged particle moves through a medium like water producing a faint flash of blue light.

The team suggest Jupiter is an ideal location to hunt for dark matter using Cherenkov radiation detectors. It’s low core temperature and significant gravitational attraction will mean it could capture dark matter and retain it.

The presence of neutrinos in the direction of Jupiter reveals the capture and annihilation of dark matter. A similar technique is used by observing the Sun.

Written by Mark Thompson/Universe Today.