A new study from the University of Mississippi shows that treated farm waste can be used to filter harmful microplastics from water runoff, reducing pollution by over 92%.

Microplastics, which are tiny plastic particles less than 5 millimeters in size, have been found everywhere on Earth, including oceans, food, water, and farmlands.

These particles are a growing concern as they can harm wildlife and potentially affect humans who consume contaminated food.

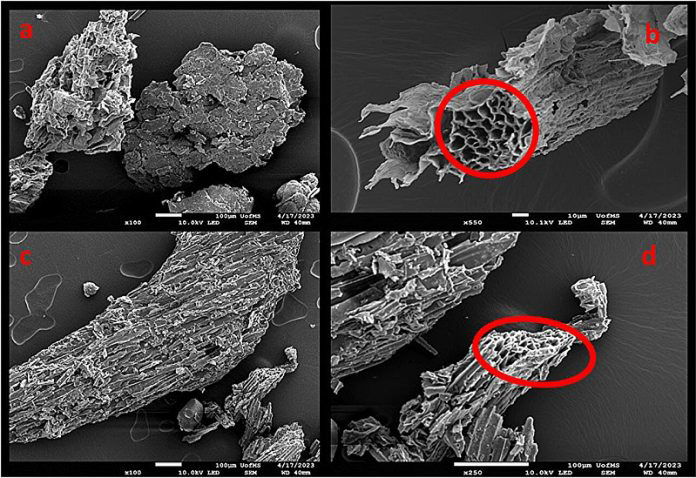

The study, published in Frontiers in Environmental Science, tested the use of biochar, a charcoal-like substance made from heated plant material, to filter microplastics from agricultural runoff.

Biochar offers a cost-effective and efficient way to trap microplastics before they reach rivers, lakes, and oceans.

“Microplastics come from the breakdown of larger plastic items due to natural processes like sunlight and physical wear,” said James Cizdziel, a professor at the University of Mississippi and co-author of the study.

“These tiny particles are a huge challenge because they persist in the environment and can build up in plants and animals, causing harm to wildlife and potentially humans.”

Microplastics in agriculture come from sources like sewage sludge used as fertilizer and plastic mulch used to insulate crops.

As these materials degrade, they break down into microplastics, which can be carried away by rainwater.

This agricultural runoff carries microplastics and other pollutants into nearby water bodies, where they pose a threat to aquatic life, including small fish and oysters. Humans and other animals that eat these organisms can also be affected.

The research team, which included Ole Miss graduate student Boluwatife Olubusoye, collected samples of agricultural runoff from a farm near Beasley Lake in the Mississippi Delta.

The runoff was then tested for microplastics at the university’s microplastic research lab. The team passed the water through filters containing biochar to see how well it could capture the microplastics.

The results were impressive. Filtering the water with biochar reduced microplastics by between 86.6% and 92.6%. Encouraged by these results, the team is now scaling up the project and testing biochar in larger field studies.

“Our research aims to reduce the amount of microplastics entering water bodies from farms and cities,” said Olubusoye.

“This is important because microplastics can travel from agricultural fields and urban areas into aquatic environments, where they can harm wildlife.”

The researchers plan to share their findings at several upcoming conferences, hoping to inspire new agricultural and stormwater management practices to combat microplastic pollution.

“Biochar has the potential to be a low-cost and effective tool for filtering microplastics from runoff,” Cizdziel added. “We believe our work could lead to new strategies that protect both the environment and human health by reducing microplastic pollution.”