Our universe is defined by the way it moves, and one way to describe the history of science is through our increasing awareness of the restlessness of the cosmos.

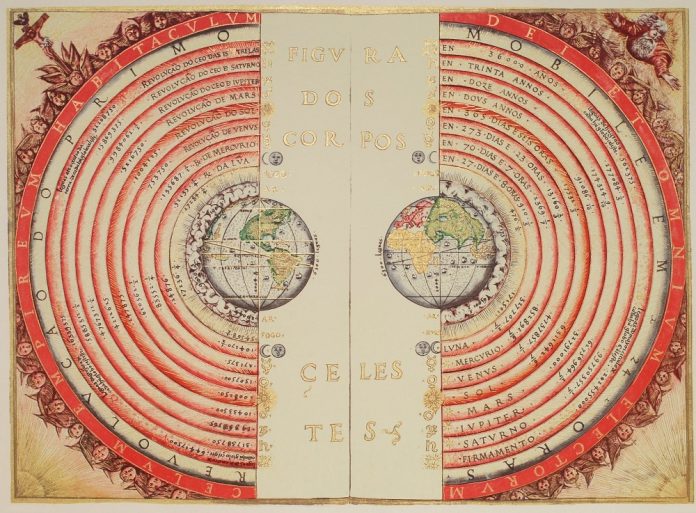

For millennia the brightest scientific minds in Europe and the Middle East believed that the Earth was perfectly still and that the heavens revolved around it, with a series of nested crystal spheres carrying each of the heavenly objects.

Those early astronomers busied themselves with attempts to explain and predict the motion of those objects – the Sun, the Moon, each of the known planets, and the stars.

Those predictions were excellent, and their systems able to explain the data well into the 16th century.

But that cosmological system of motion, initially developed by Claudius Ptolemy in the 2nd century, wasn’t perfect. In fact, it was an ungainly mathematical mess, relying on small circular orbits nested within larger ones, with some centered on the Earth and some centered on other points.

On his deathbed in 1543, the Polish astronomer Nicolas Copernicus published On the Revolutions of the Heavenly Spheres, a radical reformulation of the old Ptolemaic system that put the Sun at the center of the universe – still and motionless – with the Earth set in motion around it along with all the other planets.

The reaction to the work of Copernicus was mixed and muted. On one hand, it was a bold and controversial reshaping of the universe.

On the other, it was arguably just as messy and complicated as the Ptolemaic system it was trying to replace.

And it introduced more than a few questions that had no easy answer. First and foremost, if the Earth was moving, how could we tell?

We know we are moving on the surface of the Earth through a variety of ways. We can feel the wind against our face when we run, or watch as a distant goal draws nearer.

So why don’t we feel a great rush of wind as the Earth orbits around the Sun? Or why aren’t we flung off into the void of space due to the incredible rotation of our planet?

To all this, there were no ready answers. It would take another century and the development of Newton’s theory of gravity for the full picture to come together and make sense of the Earth in motion.

Today we know that we don’t feel the motion of the Earth because we are in motion along with it, and since the vacuum of space is just that – a vacuum – there’s nothing for us to push against and betray that motion.

Written by Paul M. Sutter/Universe Today.